Michael D. Hattem has a thoughtful review on the stagnation of scholarship on the American Revolution over at the Junto. He writes about the ways in which intellectual histories of the coming of the Revolution were preeminent in the 1960s, and then dominance of social histories of the effects of the Revolution in the 1970s and 1980s. He also writes about the call for transnational or global histories, which work against interests in writing about quintessentially nationalist events like the Revolution, and finally concludes:

I would argue that the last thirty years (and the explicit raison d’être of the conferences, i.e., the stagnation of Revolution studies) show us unlikelihood of “new directions” organically emerging from working within these paradigms. That is not the fault of the paradigms or the historians working within them since it was not something they appear to have intended to achieve. But I also do not think those paradigms lend themselves to producing the kind of consensus required to actually forge new directions in a field that has been so mired in such a deep rut for so long a period of time. To break out of this rut––to reconstruct the Revolution, as it were––will require more than that. It will require historians who care about the American Revolution as its own topic to confront our historiographical predicament head-on.

Go read the whole thing–it’s worth it, even if I don’t think he provides a lantern out of the darkness and disinterest in the Revolution. Many of the distinguished scholars he mentions have tried–and failed–effectively to re-ignite our interest. Hattem must be at least a little younger than me, because he left out an organizing event in that 1960s and 1970s frenzy of scholarship on the Revolution, namely, the 1976 Bicentennial.

The Bicentennial, for anyone who can remember it, was a Big Freakin’ Deal. Remember the national and international events of the previous two years: Watergate and President Richard M. Nixon’s resignation; President Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon; the final flight out of Saigon and the end, finally, of the U.S. War in Vietnam. 1960s radicalism ground to a parodic end with the 1974 kidnapping and conversion of Patty Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army. 1976 was also a Presidential election year featuring the never-elected either to the Vice Presidency or the Presidency Gerald Ford and the newcomer from Plains, Georgia, Jimmy Carter.

The Bicentennial, for anyone who can remember it, was a Big Freakin’ Deal. Remember the national and international events of the previous two years: Watergate and President Richard M. Nixon’s resignation; President Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon; the final flight out of Saigon and the end, finally, of the U.S. War in Vietnam. 1960s radicalism ground to a parodic end with the 1974 kidnapping and conversion of Patty Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army. 1976 was also a Presidential election year featuring the never-elected either to the Vice Presidency or the Presidency Gerald Ford and the newcomer from Plains, Georgia, Jimmy Carter.

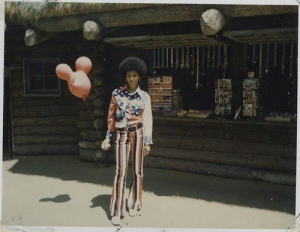

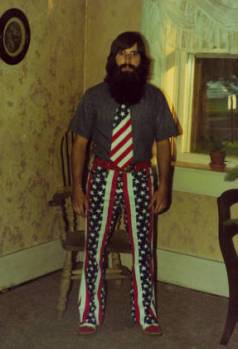

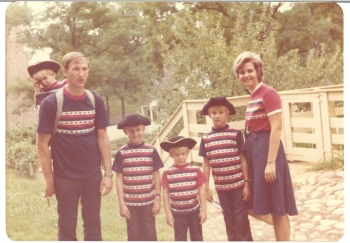

I was only seven at the time of the Bicentennial celebrations in the summer of 1976, but remember its incredible build-up through the early and mid-1970s. Colonial and Revolutionary revival was big in domestic architecture and the decorative arts. My childhood home, built in 1974, was a Ryan Home model called “The Bunker Hill,” and as I recall the other models of homes built in our neighborhood also had names like this derived from Colonial places and Revolutionary War battles. (I can’t find a link to confirm this–maybe some students of recent U.S. vernacular architecture can confirm?) The neighborhood built just a half-decade earlier than mine had streets named after a mash-up of Cavalier Virginia and Civil War battles: Williamsburg,Vicksburg, Gettysburg, Petersburg, and Fredericksburg. I grew up reading in the light of a lamp with a base like a Revolution-era drummer in the family room of the “Bunker Hill.” I remember curtains printed with eighteenth-century drums and arms, and summer tops with eagles in red, white, and blue on them. The fashions on display here in the photos speak for themselves!

Close to Independence Day, an actual wagon train of Conestoga Wagons led by horses and commanded by some overland historical re-enactors and hippies came to town and camped at Olander Park in our neighborhood. Was it they who staged the parade through town that featured a float re-enacting the Boston Tea Party, with “colonists” dressed as “Indians” throwing Lipton Tea bags at the crowd? (One of those tea bags hit me in the face! I got curious about why tossing teabags around had anything to do with the Declaration of Independence and the Revolutionary War. It was perhaps the event that made me an early American historian.) I don’t think I’m unique among scholars in their mid-40s and older; Jill Lepore has written about her memories of the 1976 Bicentennial in essays in The New Yorker which are reprinted in some of her recent essay collections, and I see a great deal of similarity in the way she and I both remember the 1970s and its engagement with early American history.

The point of this personal reminiscence is to say that I think those of us who remember 1976 and the build-up to it are not the scholars who will likely re-ignite interest in the American Revolution. Our interest in early America may have been fired by the Bicentennial celebrations, but by the time we got to college and graduate school, most of the truly important and innovative work on the Revolution had been written (or was well on its way.)

The point of this personal reminiscence is to say that I think those of us who remember 1976 and the build-up to it are not the scholars who will likely re-ignite interest in the American Revolution. Our interest in early America may have been fired by the Bicentennial celebrations, but by the time we got to college and graduate school, most of the truly important and innovative work on the Revolution had been written (or was well on its way.)

For me, it was books like John Shy’s A People Numerous and Armed; Linda Kerber’s Women of the Republic; Mary Beth Norton’s Liberty’s Daughters; Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom; Gary Nash’s Forging Freedom; Sylvia Frey’s Water from the Rock; and Al Young’s work on George Robert Twelves Hughes, for example. What was left for a young scholar to say in the 1990s after that embarrassment of riches?

My bottom line: I think it will take a fresh generation with no memories of the 1970s to revolutionize studies of the American Revolution. What do the rest of you think, those of you who remember the 1970s as well as those of you who don’t?

I wore my mom’s colonial style wedding dress for Halloween one year.

My similarly-aged (and slightly older) friends who study history are more interested in the 1960s than the 1770s.

LikeLike

More’s the pity! The trend towards very recent 20th C history is understandable given the fact that 2000 put the end to that century. I see trends now of students moving away from *one decade at-a-time* histories of the 20th C and more emphasis on continuities across several decades or centuries. Or, at least I hope that’s a thing and not just a fond hope of mine.

Thanks for the detail that you mother wore a colonial wedding dress. It was pervasive, and much more democratic (as in available in more mass-marketed clothing, consumer goods, and architecture) than the Colonial Revival of the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

LikeLike

I am apparently six years younger than you and so I don’t personally remember the bicentennial. (But from the looks of those pictures, I’m not really regretting that fact). Seriously though, I think you are definitely right that the work that was done, both in intellectual history in the 1950s and 1960s and in social history in the 1960s and 1970s, was so innovative and had such a huge impact on how we understood the Revolution, that it likely will take more remove to get to a point where we can begin to think of some of the questions anew.

And I said this in response to your comment at The Junto, but I would just like to reiterate. I don’t mean to suggest that the specific approach which I offered (derived partly from my own work) is the only (or even best) possible direction to get out of the revolutionary rut. It will take multiple approaches to do that but, most generally, it is my hope that there will be a recommitment to those questions. Thanks again for the thoughtful response!

LikeLike

I hear all of this.

I am about your age, and experienced the Bicentennial in New England, with Boston just a quick field-trip bus ride away. Man, was that an experience.

LikeLike

Rick Perlstein does a great job analyzing the bicentennial in his book _The Invisible Bridge_. As for me I had stars and stripes pants that I wore when we watched the parade of tall ships down the Hudson.

LikeLike

Michael–thanks for your response here & at the Junto. You’re not as young as I had assumed you were!

My post here isn’t critical of yours at all–I admire your boyish enthusiasm and determination! I’ve done my best to completely avoid the American Revolution, writing two books now that jump it completely by 1) ending ca. 1763, or 2) ending in Quebec in 1780. Now I’m interested in the Early Republic.

BUT, your provocative post reminds me that while **I** might not be interested in the American Revolution or see a way to contribute to its scholarship, most of my students are very interested in these issues and they don’t know much if anything about the embarrassment of riches in the 1960s and 1970s. My problem in teaching the Am Rev is that so much of our secondary lit. on this period is caught in the old “A Revolution for Home Rule, or a Revolution about Who Shall Rule at Home?” paradigm. I can’t even set up Gordon Wood any more to defend his “Radicalism” thesis, because I think it’s pretty clear that the social and cultural historians have won the debate and have whittled the American Revolution down to a fairly modest change in political circumstances rather than a truly revolutionary Revolution.

I need to get over my boredom with this debate and either find a way to fake some enthusiasm while teaching it as new (to them) material to students, or I need to find a way out of this old debate. But for all of the reasons you cite at the Junto–I just can’t see them!

Can anyone help? I mean, other than telling me to show slides of American-flag clothing on Widgeon and Dr. Cleveland (and me) as children. Actually: maybe that’s something I could do! And although The Shoemaker and the Tea Party is nothing new to me, in my experience it’s a very effective book for teaching about history and the politics of memory and of commemoration.

LikeLike

In 1976, I watched OP SAIL from 1 New York Plaza. Shortly thereafter I dressed as a Revolutionary soldier (with an authentic replica paper cut out hat and red and white striped pants for the New York State Regulars) but lost out in a costume contest to one of about 50

Ben Franklins. Thus was born a pendant. My mom wanted us to do the Wagon Train thing (which is the subject of one of the American Girl Doll books).

I took a course on the Revolution in college and loved it. Went to Fraunces Tavern and worked on an exhibit on soldiers’ lives during the Revolution (again a blast) where I got to meet Dick Bushman and John Murrin. Went to grad school at Michigan (hello John Shy!) and promptly became a post World War II Western historian. oops. I think I shared that sense of it was all done. I think looking at how the Revolution was different in different places helps me keep it fresh. My EQ is almost never “How Revolutionary was the revolution” but something along the lines of “Why was their a Revolution” with many possible answers after the because: also gets to the running theme of structure vs. contingency early in the course. But even there, I end up in a “Tragedy of Thomas Hutchinson” narrative that is almost 50 years old!

In related news, the discover that Weibe’s Search for Order is still pretty much how everyone understands Progressivism is kind of depressing and remarkable all at the same time.

For my HS students, I try to stress the “it takes two to tango” angle and explain why the British wouldn’t just give in to colonists demands. Because we are in Pennsylvania, we also look at the Pennsylvania Constitution as an alternative to what could have been for Shays’ Rebellion scared the crap out of elites.

LikeLike

Somehow my last paragraph ended up in right after the oops.

LikeLike

I believe it was originally her bridesmaid’s dress for my aunt’s wedding who got married the same year. So definitely pervasive.

LikeLike

imagine focusing on a *decade*. modernists are adorable!

LikeLike

I think there are two separate issues that you bring up here and they aren’t the same.

The first issue that you seem to have brought up is “How do we get the broader public more interested in the Revolutionary War”? Unfortunately I don’t think there’s an easy answer to this question. The simple fact is that the Revolutionary War period just isn’t exciting to most people–and I think I can say this simply by examining the number of tv shows and movies made about the period.

Since 1950 there have been maybe 10 movies made about the Revolutionary War. Three or four of those were made-for-tv movies, and a couple have been independent films.

There have been a handful of tv shows on the subject, ranging from the pretty good (HBO’s “John Adams”–which was not strictly focused on the period) to atrocious (the recent travesty from the History Channel).

I think that to engage the broader public in the subject what will be needed is a massively popular tv show or movie. Even though any such venture will undoubtedly have historical errors in them, it’s through such things that people tend to become interested in the real history. I first became interested in the Revolutionary War by watching “Johnny Tremain” (and reading the book), and watching reruns of “The Swamp Fox”.

This is the grand narrative history that Gordon Wood recently said we need more of.

The second part of the issue is “what kind of history will create interest among historians”? This is a much more difficult question, and one that doesn’t have a single answer. I think that this is where the social histories of the period are vitally important. It’s important to tell stories about women, enslaved people, the poor, the young, the dispossessed, because these stories relate to our modern times better. People don’t want to just know about “dead white guys”.

So maybe the trick here is to find a way to combine the narrative story tradition with the social histories and tell stories from the viewpoint of these people.

LikeLike

“I can’t even set up Gordon Wood any more to defend his “Radicalism” thesis, because I think it’s pretty clear that the social and cultural historians have won the debate and have whittled the American Revolution down to a fairly modest change in political circumstances rather than a truly revolutionary Revolution.”

For me, as a Female-American, it was a couple of things.

Overall, wanting to identify when young with my (predominantly male) American culture: “How Are We Different”. Well, we’re a representative government, is how I saw it then.

The feminist, visceral edge to this came through when I read up on the French revolution. It brought home to me that for the first time in Western history, the theory that the meanest street sweeper had the same right to self-rule as did the divinely appointed kings and nobles. The Magna Carta was nothing to it. This was the supposed essence, not actually realized in any way at all until 1920, of American democracy.

Western Europe was thrown into panic after panic that that theory would spread and it did. Except for the half of humanity into which I was born. We waited a full 70 years after any male in this country before being included in the theory that “All men are created equal”. That was over two hundred years after those words were written. That was my bicentennial.

LikeLike

So I’m not an Americanist (so I might be missing loads), but the most exciting thing I’ve read on the American Revolution recently (and it’s pretty good reading) is:

Nicole Eustace, Passion is the Gale: Emotion, Power and the Coming of the American Revolution, (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

The following are also great, although more about Revolution in context and application that a traditional political narrative. (However that counts for me).

Clare Lyons, Sex Among the Rabble: An Intimate History of Gender and Power in the Age of Revolution, Philadelphia 1730-1830 (2006)

Jason Frank, Constituent Moments: Enacting the People in Postrevolutionary America (Duke, 2010)

LikeLike

Nineteen seventy-six was the year I graduated high school and promptly decamped to Europe. The only sort of celebration of nation I came close to was cheering on the USA at the Summer Olympics.

Some historians see the Bicentennial as a bust overall, and I have to agree with their assessment. The Eastern Seaboard sort of had a monopoly on the celebrations–the Bicentennial Commission, created in 1966, quibbled for years about whether the celebration should be located in Boston or in Philadelphia. A lot of planned programming never got funded. Add in the end of the Vietnam Conflict, stagflation, and the general malaise of the era, and it was all more of a political hangover than anything else.

The Colonial Revival of subdivision architectural design (also true of gas stations and shopping plazas) was due more to its continued popularity of the “Phony Colon-y” from the 1950s conjoined with the interest in the past brought on by the Historic Preservation Act of 1966. (The Colonial Revival has never really gone out of style.) That act brought about the National Register of Historic Places, state historic preservation offices, and created a whole new army of professionals in historic preservation, historic architecture, archaeology, and the like.

It’s this part of social history that doesn’t really get taught as much as it should–we rely more on Gross’s The Minutemen and Their World, for example, to tell the story of the everyday changes of the Revolutionary era. But if there is a success story out of the Bicentennial, it’s that of local preservation and revitalization of historic structures and neighborhoods.

I also recall a lot of wearing of red, white, and blue flag-themed clothing as growing out of the larger debates about flag-burning by anti-war protesters and the wearing of the flag by hippies and bikers. Our school even had a debate about whether wearing a patch depicting the US flag on the back pocket of one’s jeans was a form of desecration. As avant-garde artists and designers played with the flag qua flag–overlaying with peace signs, for example–more mainstream designers were churning out red, white, and blue designs that “honored” the flag–even down to the optional fringe.

Sorry to get all material culture on you. This is the sort of stuff, however, my students could more readily apprehend out of their own experiences and then understand the Revolution. It was a lot more successful to teach why a dockworker and George Washington would want a revolution, and on what different premises (no pun intended).

LikeLike

@john- have you seen “The Book of Negroes”? Probably a bigger deal for us at an HBCU, but still- it takes place partly during the Revolution, it was just on tv, and it’s quality historical fiction.

LikeLike

I was eight when we celebrated the bicentennial. My family spent the better part of the summer and the fourth of July in my Dad’s home town in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. I think I saw the Northern Lights for the first time. I remember the red white and blue themed outfits and we made parade floats from cardboard boxes, bicycles, streamers, and wagons. It was a great parade and family reunion. That is the Social Memory of the American Revolution for me.

I guess I don’t understand the point of Hattem’s essay. I understand that the interest in some topics ebbs and flows like the tide. The idea that you can hasten that popular and scholarly enthusiasm seems a little misplaced. My own experience studying the topic as an undergrad was tedious, but I never had a strong personal attraction to American History. Right now, as a disinterested observer and American citizen, I think the period from 1830 to 1860 seems more interesting and in tune with what is going on in contemporary American politics and society.

I doubt that the study of the American Revolution is in any imminent danger of becoming irrelevant or underfunded. I specialize in modern Eastern and Central Europe (ECE). In the decade after 1989, during the so-called transition era, Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union was hot, hot, hot! But now there is very little popular or scholarly interest outside some established centers like Indiana, Columbia, Berkeley, Michigan, and Chicago. The History of the American Revolution seems to have a steady market.

Some of the research paradigms of ECE seem played out, or at least a little tired. For example, Nationalism was a big thing in the 1980s and 1990s and now it seems to be fizzling out into National Indifference, although Tara Zahra just landed a MacArthur fellowship for her excellent work in this area. There is a huge Nationalities conference every year in New York, but honestly its mostly Kuhnian “normal science” elaborating new examples of existing concepts. Maybe the American Revolution just has to bump along the road of normal science for a while until a grad student comes up with a new paradigm. (I don’t know if thats the best metaphor for changes in historiography, its just the best I can do on one cup of coffee…)

LikeLike

Nothing to say about 1976 Bicentennial celebrations, but the historiographical dimension is interesting to me because there was a similar kind of crisis in the history of the French Revolution after the big wave of work inspired by the French Bicentennial blow-out of 1989. Another big part of the problem there was the collapse of the Marxist interpretation with the end of the Cold War. Once the revisionist view put forward by cultural historians had run its course in the 90s, it wasn’t clear what the stakes were anymore. The current financial crisis and global capitalism finally seems to be providing a way out of the doldrums by fueling new research on the economics and global connections of the 18th century and Revolution.

LikeLike

Wow–thanks everyone! I’m loving all of these perspectives on other tired historiographies, as PDXPat, Ellie, and Matt are pointing out.

John, in point of fact, I don’t really care whether or not the American Revolution has a popular audience, and I never raised it in my post. (Maybe you read my memories of the 1970s as nostalgia, but it was merely my view of the social and material history of the era.)

If Americans are going to be interested in any point of early American history, it’s going to be the Revolution. All of the popular movies and entertainment you cite are nearly the ONLY representations of early America in movies or TV series in the past 20 years (other than Pocahontas, the Disney version, and that New World excresence with Colin Farrell which was, not coincidentally, another telling of the Pocahontas story.) The American Revolution, as Matt implies, is OK in terms of public esteem in the U.S. (Quite frankly, I think that’s what makes it so damned boring for me to teach.)

History Maven: thanks, as always, for lending your expertise! I think you’re right that colonial revival has really never been completely out of fashion in terms of vernacular architecture and material culture since ca. 1890 or so.

Western Dave is right that a global approach is probably the best way to teach this stuff. But I just can’t get over my own lack of expertise outside of North American history, so I haven’t been able to get excited about teaching comparative 18th & early 19th C Revolutions. Because my next research project will demand some attention to Revolutionary, Republican, and Napoleonic France, that may change in the next few years.

LikeLike

This may be an ignorant remark, but is there anything in American History that has been analyzed any more exhaustively than the revolution? And if so, then wouldn’t it be more fruitful for American historians to focus on something else? Like, I guess I’m not getting why a resurgence of work on the revolution is something that ought to be encouraged?

LikeLike

THE CIVIL WAR! Also, WWII for a close second. The scholarship and popular interest in both of these far outweigh those on the Revolution.

But, it’s a good question. I’ve decisively answered “yes” in my own scholarship to your question, “wouldn’t it be more fruitful for American historians to focus on something else?” But there’s value in revisiting old ground to see if we can plow up anything new. At the least, it’s the one subject in early American history that people have heard of and may have some interest in.

LikeLike

Don’t guys like Cliven Bundy own the popular meaning of the American Revolution these days? I was on my way out of elementary school at the time of The Bicentennial and I guess I remember some of the trappings, especially America Rock.

And the shot heard ’round the world

Was the start of the Revolution

The Minutemen were ready, on the move

Take your blanket, and take your son

Report to General Washington

We’ve got our rights and now it’s time to prove

Personally, what interests me about the Revolution(s) (American and French) is how they appear abroad, in poetry and other artistic expression.

These fifty years he’s steer’d the helm,

A time, nae doubt, o’ great alarm,

But here we’re a’ wi’ little harm,

Our pilot dainty Geordie.

from Dainty Geordie

LikeLike

I was too young to remember the bicentennial, but I did grow up from age 7 on in a colonial-style home built in the 1970s. Now, in Massachusetts, it seems like every other house is colonial style, but I do notice that housing developments built in the 50s and 60s tend to be more single-story ranch style, while in the 70s both 2 story colonial and split level became the standard. I have no idea if this was related in any way to the bicentennial or not.

One thing I was curious about – how does the American Revolution being relatively well-known and popular make it a boring subject to teach?

LikeLike

Pingback: Generation Gap | Kitty Calash

I’ve been thinking about Comrade PhysioProf’s question and it turns out that there is something under examined even in World War Two historiography: Lend Lease. I was working with a student on her Senior Seminar thesis and she wanted to do a paper on Lend Lease. There were two problems:

First, It turns out that the primary sources were more difficult to find than we expected (unless you’ve got a month or two to go to the National Archives in College Park. Thats a deal breaker for an undergraduate trying to get it done in a semester.

Second, there was hardly any new scholarship since the 1970s, except for one monograph published in the mid-1980s. None. I looked, she looked, our research liaison in our library looked (and he is our government documents expert to boot). None of us could find scholarship on Lend Lease after the 1980s. Zip. Nada. This is striking because there should be a whole host of new material available after the collapse of the USSR and the opening of the archives in the 1990s.

So believe it or not there is at least one part of WWII that is due for a reappraisal. The only catch, you have to be a US historian who could read Russian. And if you are a PhD student who studies the US during Cold War, you really ought to have to pass a language exam in Russian and Spanish before you take comps. Just saying 😉

LikeLike

A couple of thoughts:

1. It might be useful to consider that it is somewhat different to “focus on the American Revolution” or on the revolutionary war, than to consider the relationship of the Revolution (war or longer process) to what came before or afterwards. I agree with Historiann that a younger crowd will determine the future of the field, but I wonder if the creativity _and_ the problems of the field have really always come from the necessity and the limits of such questions about the Revolution’s long-term roots (its relationship to colonial development, stressed most recently and with great geographical range in Thomas Slaughter’s Independence [2014]), and long-term results, i.e. democracy or capitalism for Gordon Wood; racism and expansion as well as nationhood for others. Colonial Americanists have long had a fraught relationship to the Revolution, for which which the Atlantic turn provides needed relief, i.e. you can approach the Revolution from some other vantage points. The recent conference calls to which Michael Hattem refers have bewailed a lack of interest or creativity in studies of the Revolution, but perhaps those jeremiads stack the deck by construing “the Revolution” too narrowly, leaving themselves open for a critique like Hattem’s. Of course few will care if it is only about 1775-1783 (despite the relative neglect of the war until recently); of course no one is impressed if we retail facile and easily critiqued Bancroftian bromides about how the Revolution simultaneously was inevitable outgrowth of hundreds of years of New World history …..and yet also created everything ‘modern’ and subsequent about the United States. It’s the founding dilemma of the field that at its most ambitious and occasionally at its best it is parasitical, temporally and historiographically speaking, on everything else.

2. Can anyone say tea party? (It used to be, can anyone say revolution?) There continue to be big political stakes in how we depict the Revolution and in how we cast its relationship to much else, for both historians and the public. That is the real source of the “problem,” if it is a problem. The rest, as Historiann suggests, can be described as typical cycles of attention. The larger stakes in the culture war have received particularly good analytical attention recently from Jill Lepore and Andrew Schocket in his new book, Fighting Over the Founders (NYU Press). Indeed, Schocket’s stimulating book should remind us that the contested memory of the Revolution is too important to leave to public historians who do not actually study the period. Perhaps in the future some of the creative dialogue will come from a conversation between those who study the memory and uses of the Revolution and those who study the period – making more explicit what has often been implicit.

3. One might argue that the most original and controversial new interpretations of the Revolution are those that put the problem of slavery at the center of the Revolution, rather than depict “the problem of slavery” as an after-effect. That’s what Gordon Wood has in mind when he says the profession is going to hell. (See most recently and nastily his review of his mentor Bailyn’s most recent collection of essays, or his introductory remarks in own recent collections such as The Idea of America.) Woody Holton and Robert Olwell and Sylvia Frey began this trend during the 1990s. But this trend, which has by no means achieved the status of a consensus while traces begin to be seen in textbooks in the increasing attention given not only to Africans but also to Somerset’s Case, has never received sustained historiographical discussion, perhaps because we are still at the beginning of it. Several papers from next week’s MHS conference seem to continue the inquiry.

LikeLike

Thanks, David, for your thoughtful comment. I’m sorry it’s taken me a few days to return to this thread to respond. It’s interesting to read it again in light of the live-Tweeting of Woody Holton’s keynote address at the MHS conference on the Revolution today (#RevReborn2).

I think you’re right that historians like yourself who have worked on slavery as central rather than marginal or peripheral to the Rev. have probably done the most recently to advance something new in the field.

Jill Lepore’s recent book (2011?) on the Tea Party, and the lengthy New Yorker article that served as a rough outline for the book, were very good on the subject of the Revolution in memory and history. I have to agree a little bit, however, with Gordon Wood (!) in his review of that book in the NYRB, in which he (fairly) accused her of a lack of sympathy for right-wing uses of the history and memory of the Revolution. While she acknowledges that every generation gets the American Revolution it deserves and acknowledges that memory is always selective, I too thought that she was unfairly dismissive of the modern-day Glenn Beck-style Tea Partiers.

I still think that Al Young covered that ground really well in his The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, in the second half in which he talked about all of the different movements that have deployed the symbolism and memory of the Tea Party as a way of glorifying and justifying their own causes.

LikeLike

To which (Shoemaker) I would add Charlene Mires’s _Independence Hall in American Memory_ (2002).

LikeLike