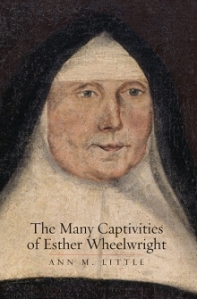

Esther Wheelwright, c.1763 (oil on canvas), 55.7×45.5 cm; © Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

It’s Esther Wheelwright’s 321st birthday! She was born March 31, 1696 (Old Style).* Since Esther has been dead for 237 years, I was thrilled to accept a birthday present on her behalf in the form of a rave review of my book, The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright, at the Christian Century! (H/t to friend and blog reader Susan for passing it along.) In “Women Who Do Things,” Margaret Bendroth, the executive director of the Congregational Library and author of The Last Puritans: Mainline Protestants and the Power of the Past (among many other titles), gets my book exactly right. Check out her lede, which is just perfect:

An offhand remark can change everything. I still remember a graduate school professor’s consternation at the idea of “women’s history.” “They don’t do anything,” he protested. The comment passed without notice in a room full of male professors and students, but it took up permanent residence in my head. I was hooked, not just by his attitude problem but by the nagging reality that in the categories this well-regarded historian recognized—wars and politics and all that—he was right.

Writing women into history isn’t easy. It’s one thing to add an occasional sidebar in a textbook or praise a heroine whose brave exception proves the rule, but that doesn’t change the overall story line. The narrative still belongs to men who “do things,” driving the engines of change by waging wars and winning elections.

I am so touched that readers and reviewers really get where I’m coming from, and are moved to share their own stories of alienation and feelings of displacement in graduate school. The discipline of history isn’t just heedless or careless about women and women’s history–it’s actively engaged in denial and erasure.

Ann M. Little, who teaches history at Colorado State University, has taken on this challenge. Her massively and meticulously researched biography of Esther Wheelwright—born of Puritan stock, then Wabanaki captive, and finally French Catholic nun—is a story of politics and war in 18th-century North America, with women at the center. Much of the landscape is familiar: conflicts between colonial powers and cycles of frontier violence. But ultimately this is a story of one woman and, more importantly, the communities of women and girls “who surrounded her at every stage of her life,” Congregationalist, Wabanaki, and Ursuline.

Little reconstructs Wheelwright’s life mostly from offhand sources, often forced to rely on tantalizingly brief references in official accounts. Even so, the story is gripping.

I can’t go on, or I’m going to get a swelled head, so you’ll just have to go read the whole review yourself and try, try if you can to resist buying the book or ordering a copy for your local public library or your college or university library.

And wait–there’s more! I was reminded today by a Tweet from the Declaration Resources Project that March 31 (New Style) is the date of the letter in 1776 which Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, who was in Philadelphia at the Second Continental Congress:

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency”. Her letter of March 31st continues, “in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to forment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

Abigail Adams was connected to Esther Wheelwright in other ways beyond the events of two Marches the 31 separated by 80 years. I was alerted by Woody Holton when he was writing his biography of Adams that she, when still Miss Abigail Smith, was given a letter in french to translate that was by none other than Mother Esther de l’Enfant Jésus, the former Esther Wheelwright! Here’s what I say in my recent book about the translation exercise and its significance:

Mother Esther’s fame as mother superior spread through parts of New England beyond her family circle. Eighteen year-old Abigail Smith, during her courtship by future U.S. President John Adams, wrote a letter to her cousin Isaac Smith in which she told him that “by the favor of my Father I have had the pleasure of seeing your Copy of Mrs. Wheelwrights Letter, to her Nephew, and having some small acquaintance with the French tongue, have attempted a translation; of it, which I here send, for your perusal and correction.” (Smith uses the honorific “Mrs.” as an abbreviation of the honorific “Mistress” offered to high-ranking colonial American women whatever their marital status.) Historians have assumed that this was a letter that Joshua Moody brought back from his visit to his aunt in 1761. If copies of the letter circulated, it was almost surely because of Mother Esther’s stature in the British-occupied city of Québec rather than the want of French-language materials for students in Massachusetts. Her conversion to an enemy language and religion was perhaps viewed as less threatening now that she and all of her sisters in religion would live once again under British rule.

Unfortunately, the translation is no longer attached to Smith’s letter, but

a postscript to her letter suggests that Mother Esther’s sex was of special interest to Abigail Smith. In particular, Smith is fascinated by the gender

politics of religious women, suggesting to her cousin, “N B. How the Lady abbess came to subscribe herself Serviteur [servant], which you know is of

the masculine Gender I cannot devise unless like all other Ladies in a

convent, she chose to make use of the Masculine Gender, rather than the

Feminine.” In March 1763, Mother Esther was completing her first term

as mother superior, and would be elected to another term that December. The few letters we have in her hand date from that period, and unfortunately, only two out of three preserve her original signature, which was “Votre tres humble et tres obeissante servante Sr. de L’enfant Jesus”—Your very humble and obedient servant Sister of the infant Jesus. In one case she omits the feminine “e” at the end of “servant,” but Mother Esther never uses the word “serviteur.” Perhaps the words “servante Sr.” ran together in Smith’s eyes to resemble the word “serviteur.” Contrary to Smith’s claims that “all other Ladies in a convent . . . make use of the Masculine Gender, rather than the Feminine,” Ursuline nuns conformed to the grammatical conventions of the French language and used the feminine forms with reference to themselves and others when appropriate. Smith was wrong in her guesses about Esther’s signature and the kind of masculine authority she may have assumed or presumed as the mother superior of the Ursulines. But Smith’s letter is proof that in her old age, Mother Esther had become an object of fascination and an example of female independence and achievement for protestant Anglo-American girls like her nieces and grand-nieces.–The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright, 224-25.

Now isn’t that a kick in the breeches? Mother Esther could not have hoped for better missionary outreach into the heart of Congregational New England than to have her letters circulating in that crowd, recommended as lessons no less!

Finally, I have three Amazon reviews! Two five-stars, and one two-star review. Wanna guess what was bugging Mr. or Ms. Two Stars about my book? Please allow me to quote the review in full:

The basic facts are presented accurately. The writing is good, and the life and times of Esther Wheelwright make for an interesting story. . Unfortunately, the writer imposed a twentieth century feminist viewpoint on the story of a woman born in 1696! This distracts from the story and provides a skewed interpretation of her life and times. I was disappointed in this book. If you are interested in the life and times of Esther Wheelwright a better choice would be the book written by her descendant Julie Wheelwright.

I won’t say that’s not a fair review–he or she says that the research is accurate and the writing is good, and I do say clearly that my interpretation of her life is an openly feminist one. We just disagree on the value of feminism. Those of you who have read the book–for class, for research, or for fun–and who see the value in feminist analysis, please consider writing an Amazon review that offers another perspective.

I think that’s just about a perfect way to end this blog post, don’t you? From Margaret Bendroth’s graduate professor insisting that women “don’t do anything!” to the claim that feminism “distracts from the story and provides a skewed interpretation of [Wheelwright’s] life and times.” Or, to borrow the words of another great American women, reviewing the performance of yet another great American woman, these reviews of women in history “run the gamut of emotions, from A to B.”

*Don’t bother with the lectures about how her birthday was “really” April 10. Yes, I know we’re now on the Gregorian Calendar–maybe I’m out on a limb, but I find all of that date-switching and converting from the Julian to the Gregorian Calendar more than a little pedantic, not to mention pointlessly confusing. Measurements of time are all human-made, and imprecise, so unless you’re a climate scientist or a climate change historian, who cares that the world lost 11 days back in 1752?

(In my work, I always use the day and month listed in historical documents as I find them, and I always date the new year as beginning on January 1, because all of that double-dating nonsense between January 1 and March 25 is also pointlessly confusing to modern readers.)

Besides, in the course of my research I learned that news of the change to the Gregorian Calendar came very late to the Ursulines of Québec. I think they made the switch only in the mid-1750s sometime, probably urged on by the invasion of French and British soldiers in yet another global conflict.

OMG the freaking Julian and Gregorian calendars were my nightmare in a book where some people were living in a Julian world and others in a Gregorian world and writing to each other and reading articles in newspapers from different countries and referring to battles and proclamations and other events. At first I did dual dating for everything but the reviewer (wisely) told me to cut it out.

Congratulations on the fantastic reviews! I love the beginning of that CC review; it’s an argument I suspect we will have to have over and over for the rest of our careers.

Very cool story about Abigail.

LikeLike

HAhaha! Glad to know I’m not the only historian to say “nuts to your Old Style/New Style conversions!”

LikeLike

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of March 26, 2017 | Unwritten Histories

Hello, I’m Faceless and Twitterless, but wanted to bring your attention to two items pertaining to historians’ discussions of Trump Administration policies, gender, and immigration:

Landon Storrs’ article comparing the Red Scare and Trump’s attack on the federal civil service:

http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/03/history-trump-attacks-civil-service-federal-workers-mccarthy-214951

UNC Press will have a blog series this week by immigration historians (including myself) on the roots of many of Trump’s policies and rhetoric.

LikeLike

I went to order your book for our library and discovered that we already have it!

Russia stayed with the Julian calendar all the way until 1918, when the Bolsheviks finally converted. We use dual dating for the revolutions (since the “October Revolution” occurred in November) but drop it once we get to 1918. I think that historians of Imperial Russia just automatically convert.

LikeLiked by 1 person