Baby in Blue, ca. 1845, William Matthew Prior.

National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Max Nelson offers a fascinating overview of a current exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, “Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America.” I find this subject both touching and horrifying, especially considering the understandable impulse to commemorate lost children. But as Nelson notes (per the exhibition), the practice of painting or sculpting the recently deceased continued long after the invention of photography and the democratization of family portraiture. In fact, “mortuary photography”–photographs of the recently deceased, especially babies and children–was a big chunk of the business in early photography.

There’s a painting I’ve been using in my classes to illustrate the changes in how free Americans envisioned marriage and family life from the eighteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The Ephraim Hubbard Foster Family presents such a lively contrast to the dour mid-eighteenth century puritan portraits of husbands and wives–the fresh, blushing complexions! The number of children, who appear to have been painted as individuals! The focus on parental youth and beauty! I’ve wondered for a long time if the child so extraordinarily costumed on the window sill is in fact a dead child, but having reviewed the online images this exhibition offers, I don’t think this is the case. Here’s the portrait:

The Ephraim Hubbard Foster Family, 1824, by Ralph E. W. Earl.

Cheekwood Museum of Art, Nashville, TN.

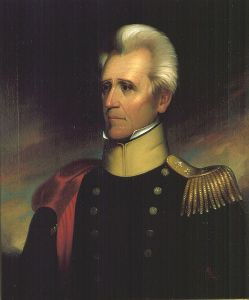

Andrew Jackson by Ralph E. W. Earl, 1837. Image from Wikimedia Commons

The child at center appears so much more lifelike than the dead babies and children in the American Folk Art Museum’s show. Just noodling around in Google books, I’ve found some family genealogies but can’t confirm the death of a child around 1824. Moreover, the little I’ve read about the artist, Ralph E. W. Earl, suggests that he wasn’t likely to have been a painter of the dead. According to Nelson’s article, these painters were likely to be untrained, while Earl was a European-trained artist who studied with John Trumbull and Benjamin West, as well as the son of another early American portraitist, Ralph Earl.

I’d like to do more research on this portrait, as there doesn’t seem to be a lot of scholarship on it or on the family outside of Tennessee and Alabama genealogical circles–this in spite of the fact that Ephraim Hubbard Foster served twice in both the House of Representatives in Tennessee and as a U.S. Senator. The artist who painted the Foster family portrait also painted several iconic portraits of Tennessee’s most famous politician of the early U.S. Republic, Andrew Jackson.

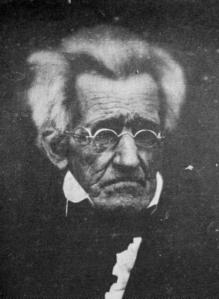

Andrew Jackson, 1845. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The Fosters look a hell of a lot more lifelike than Andy J. does! He looks pretty waxen in the portrait above, although I’m sure it was a flattering portrait of the man, who upon leaving the presidency had nary a tooth in his frequently-abscessed head, and suffered from a variety of other disfiguring ailments resulting from heart disease and tuberculosis. At left is an image taken in 1845, the year of his death at age 78. He didn’t look a day older than 135!

I wish I could get to the American Folk Art Museum to see this show before it closes in February, but I won’t. The AFAM is a little jewel that I’m afraid gets overlooked amidst the hoarde of art and cultural treasures stashed in NYC. I remember going there nearly 30 years ago in college and being really impressed–with their collections, the intelligence and historical scholarship that went into their curation, and *poor student tip*—admission is free of charge! Beat that.

And if any of you have ideas for me about the Foster family portrait, please let me know. For years I’ve regretted not studying more art history in college. I may just have to figure it out and become one myself.

LikeLike

I just canceled a swing through NYC for museum-going (to see another master of the portrait, Kerry James Marshall) and now I’m regretting changing my plans–this exhibition looks terrific! I have such fond memories of the Folk Art Museum @ Lincoln Center; my mother is a quilter, and my parents took us there every fall when I was growing up. That’s a lot of Henry Darger to see at a young age — no wonder I’m a historian of women and gender and sexuality!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Get down there! You’re not coming to Denver this weekend so NO EXCUSES!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Compare this 1832 family portrait by Louise Henry, Emil du Bois-Reymond’s aunt. Emil is the 16-year-old writing at the table. Louise is holding a portfolio. Emil’s dour Calvinist parents are on the right. Neuchatel castle (the home of Emil’s dad) is in the background:

http://www.art9000.com/poster/en/artist/image/louise-henry/18672/1/124177/the-family-of-royal-pruss–secret-counc–felix-henri-du-bois-reymond/index.htm

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Hmm, a few thoughts on this. First, you might find the exploration of this painting interesting: http://americanart.si.edu/education/insights/pictures/leclear/. Claire Perry’s Young America: Childhood in 19th-century Art and Culture would also be useful. Another source to check out (although focusing a bit later) is Domestic Bliss: Family Life in American Painting, 1840-1910. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a child quite like the one here, but there must be an expert out there who has! Honestly your best bet would probably be to contact the Cheekwood and ask if they have a research file on this painting, which they very well might.

As for Foster himself, there’s definitely not a lot out there on him. The BDAC is pretty thorough and they only list a few things: http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=F000302

LikeLike

Thanks for this, Cassandra–I’ll look into it. The child is extraordinary!

LikeLike

I’m struck by the kid in yellow, leaning on his dad. He seems like the real contrast here, especially to the kid in the window. His paleness seems accentuated, his eyes a bit crossed. I wonder if this is just a true portrait of him (kind of like George Whitfield’s crossed eyes), or if it’s done to elicit sympathy? He kind of reminds me of the frail people who dot romantic literature.

In any case, I use the portrait of Elizabeth Freake and baby Mary in my classes to talk about Puritanism. It gets students going early in the term, when they’re anxious to try their hands at image analysis, because you can playfully refer to the portrait as the Freake family (they find this hilarious). I have them discuss how we know the Freakes are doing well–usually at least one notes the importance of being able to have a portrait painted; and we also use it to discuss how Puritans saw kids as tiny adults–there’s no way on earth that baby could stand as she does, but lo! http://www.worcesterart.org/collection/Early_American/Artists/unidentified_17th/elizabeth_f/discussion.html

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your comments! Great observation on the boy in yellow–I hadn’t noticed the eyes. It’s even more interesting to me that he’s painted in the same bright silk that his mother is wearing. There’s an interesting gender reversal implied in his color link to his mother, and the baby in the window is linked to the father as they’re the only subjects who meet the viewer’s gaze head-on. Otherwise, the family is grouped according to the gender conventions of later 18th C-early 19th C family portraits, with boy children aligned with the father and the girl children/youngest baby of whichever sex aligned/in contact with the mother.

Baby Mary Freake isn’t standing up! Her torso was undoubtedly straightened by stays already, which may help explain her stiff position. (The painter’s skill was also a factor, to be sure.) I disagree that Anglo-Americans or even puritans saw children as little adults–they were viewed as having some obligations that we would now see as adult (e.g. the burden of original sin!), but the newest interpretations of the history of early American childhood suggests that babies and children were very much viewed as existing in a different phase of life than adulthood. (I wrote about this in Nick Syrett’s & Corinne Field’s 2015 edited collection, Age in America.)

LikeLike

One of my younger sisters — oddly enough, also named Mary — walked at 6 months. So depending on how old Mary Freake was at the time, it’s possible she could have stood. But it’s more likely, I’d guess, that it was an artistic convention. Or, as Historiann mentioned, stays.

I’m long out of college, but I find the Freake Family hilarious, too. Gives me comfort and hope that the younger generation has the same screwy sense of humor. Some “advancement” is overrated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, now I know what museum I’ll try to get to next weekend in NYC. I love the American Folk Art Museum and this seems really really interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

On this subject in general, in a different medium (photography), and later in the 19th c., c.f., Michael Lesy, _Wisconsin Death Trip_, (1973). Based on a Rutgers dissertation, I think, back when dissertations tended to be typed on onionskin paper and properly devoted to telling the stories of politicians who only seemed dead, it caused quite a stir, and even debate over whether it was “history.” There is even a long Youtube documentary (1999) based on the book, that you can see. Lesy got a job, when practically nobody else was, I think at the U. of Louisville, and thus the last laugh on his former committee. And helped to put the subfield of photographic history on the map. The book was pretty weird, though.

LikeLike

Correction: Lesy’s second book was about Louisville, also a photographic history. He has taught at Hampshire College, in Massachusetts, for several decades . He also wrote a book about the history of family pictures, which may be relevant here.

LikeLike

I found a record of Ephraim McNairy Foster , son of E. H., dying in 1827, age 3, so that’s probably the infant in the painting.

LikeLike

Well done! Too bad for the little baby, but there’s proof that it’s not a postmortem portrait of him at least. Moreover, he seems a little incidental compared to his fancy sister on the windowsill.

LikeLike

I’ll poke around more over the weekend – I like puzzles. Mother’s name was Jane, conflicting records on surname, probably married in 1817.

LikeLike

Catherine–you don’t have to do this! But I’d be grateful for any intel you can find. Citations most appreciated!

LikeLike

Results so far – there is still a missing child, but I agree with you that it’s probably not a dead one at the time of the portrait.

Robert Coleman Foster (b. 1818) is most likely the boy on the left. William Lyle Foster (b. 1820) is the cock-eyed boy in yellow, and Ephraim McNairy Foster (b. 1824) is the babe in arms.

There are records for a daughter Jane Eleanor Foster (b. 1821, d. 1851 aged 29), known as Ellen in later life. I’m thinking she’s the fabulous feathered child, because the girl at her mother’s knee has more hair than a toddler would (look at the ringlets!) and is holding a recorder. It looks to me as if she could be kneeling – William’s legs are obvious, but hers are not.

Phantom girl could have been born in 1819. My family’s birth separation was a pretty steady breast-feeding interval of two years, but the Fosters definitely owned slaves in 1830, so wet-nursing around 1820 was likely an option. The 1820 census records for Tennessee are unfortunately spotty, otherwise an infant girl would at least show as a tick mark on the record.

There is of course a gap in births between 1821 and 1824, but the girls in the portrait don’t seem to fit in age.

The sources are a transcript of the family bible, which had pages torn out by Union soldiers during the Civil War (Battle of Nashville, 1864?), so lots of folks are missing; Tennessee marriage records; and an assortment of tombstones. I’ll email you a link to the tree.

LikeLike

Wow–thanks so much for running this family down, Catherine!

LikeLike

Puzzles rock! I’m remembering that great graveyard-and-gravestone post and comment thread here from Michigan a number of years ago (2009?). I looked for it recently, and the header is there, but most of the content didn’t load for me, for whatever reason. One of my favorites, though. Some snow on the ground. The slatey-gray look of the old headstone stone. The “figure it out, kid,” indifference of the worn lettering on the stone.

LikeLike

What a memory! Here’s the post:

https://historiann.com/2009/12/22/a-family-history/

Kind of like that short story in 6 words that Ernest Hemingway suggested: For Sale. Baby Shoes, Never Worn.

LikeLike

Hello,

I wanted to say that the little girl standing on the table at the center of the Ephraim H. Foster family portrait was not a dead child. Her name was Jane Ellen Foster and was my great-great grandmother. She was born in 1821 and died in 1851, when my great-grandmother Susan Saunders Cheatham Jones was 6 years old. She died young, but without a doubt reached adulthood! My aunt had a beautiful portait of her that always hung in her dining room. Google Jane Ellen Foster, images, and you’ll see a picture of that portait which now belongs to a first-cousin. In the Foster family portrait, my great-great-great grandmother, Jane Mebane Lytle Foster is holding a baby-the baby was actually painted into the portait because Jane was still pregnant with it when the portait was painted. Just wanted to let you know.

Margaret Brandon

Nashville, TN

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Ms. Brandon–THANK YOU SO MUCH for commenting! My students and I have wondered about this for years now. I will follow up on your information! Thanks for your generosity in sharing this with me, and apologies for not acknowledging your comment sooner.

LikeLike