It’s an old-fashioned early American smackdown over at the Omohundro Institute blog: William and Mary Quarterly editor Joshua Piker engages Gordon Wood’s critique of the journal–and the wider field of early American history and culture. While waiting 11 months to respond to Wood’s comments is a rather leisurely pace for an online publication, Piker’s blog post suggests that waiting may have been a good thing. In his comments on Wood’s vision for early American history, I see echoes of a contemporary political argument.

First, a reminder of Wood’s comments from last winter in The Weekly Standard:

Almost a year ago, . . Gordon Wood published a review of Bernard Bailyn’s Sometimes an Art: Nine Essays on History. In this piece, Wood heaps praise on Bailyn and criticism on the field of early American history, including theQuarterly. The review includes the following paragraph:

“For many [early Americanists], the United States is no longer the focus of interest. Under the influence of the burgeoning subject of Atlantic history, which Bailyn’s International Seminar on the Atlantic World greatly encouraged, the boundaries of the colonial period of America have become mushy and indistinct. The William and Mary Quarterly, the principal journal in early American history, now publishes articles on mestizos in 16th-century colonial Peru, patriarchal rule in post-revolutionary Montreal, the early life of Toussaint Louverture, and slaves in 16th-century Castile. The journal no longer concentrates exclusively on the origins of the United States. Without some kind of historical GPS, it is in danger of losing its way.”

Piker breaks down Wood’s cherry-picking like this:

What do these pieces have in common? Geography is part of the answer. The journal is “losing its way,” Wood says, and “[w]ithout some kind of historical GPS” we might wind up in Peru, Canada, Haiti, or Spain, rather than remaining within the geographic limits of the modern United States. But geography isn’t the only answer to that question. Language is another. All of these essays focus on non-English speakers. And when you look at what articles didn’t make Wood’s list from the Quarterly’s 2012 and 2013 offerings, it’s even clearer that his category of selection privileged language as much as geography.

What essays didn’t make the list? Well, let’s leave aside the fact that, in picking these four examples from among the essays published by the Quarterly in 2012 and 2013, Wood had to winnow out a number of articles—forums on mercantilism and the ratification of the Constitution, essays on Common Sense and the structure of the British Empire—that clearly fit within the bounds of his preferred historical project: exploring the origin of the United States. Given the nature of the argument he’s making, perhaps those pieces should’ve been acknowledged? But doing so would have undermined at least part of his polemic, and so it’s not surprising that they weren’t included.

But Wood also didn’t choose to criticize the decision to publish articles that focused on the British experience in the Caribbean or Africa, even though those places are clearly outside the boundaries of the United States. And he likewise didn’t list essays dealing with French speakers in Illinois and Louisiana, or Spanish speakers in Florida, or Cherokee speakers in Tennessee.

So, if we combine what Wood included and what he didn’t, we come up with a pretty simple two-part rule for what the Quarterly should publish: If you spoke English outside what is now the United States, you’re eligible for incorporation into early American history; and if you spoke anything at all within the bounds of the modern U.S., then you too can be part of that nation’s history.

I find it difficult to characterize that sort of approach to early American history. It’s parochial, but not entirely; it’s ethnocentric, but not exclusively. Mostly, it seems confused, arbitrary, and—given Wood’s preferred project of focusing on “the origins of the United States”—self-defeating.

As I read Piker’s response, it seems like he’s responding to the Donald Trump vision of the United States as much as to Wood’s review: “Wood uses the United States as an argument for limiting the horizons of early Americans and restricting their conversations in ways that do violence to their experiences and understandings. He turns the nation into a screen that allows us to see only certain places and a filter that permits us to hear only some voices. And then he asks how, given this subset of places and that limited number of voices, Wood’s own United States came to be.”

In other words, Piker argues that Wood offers us a political teleology, not an intellectual argument about the scope and scale of early American history. (Wood can’t possibly object to any inferences about the political nature of his argument. After all, he published his book review in The Weekly Standard, a neoconservative magazine!) Wood’s early America, like Trump’s modern United States, is a world in which English is the only language that counts. It’s a world in which people who speak other languages are simply un- (or anti-) American. It’s a vision of a nation–better yet, a tribe–whose borders are vigilantly policed. Wood sees an early America, like Trump sees the modern U.S. as contaminated by other languages and cultures, in need of purification or cleansing.

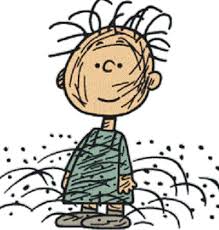

Well, nuts to that. Who demands that history be sanitized like that? Who is uncomfortable with the essential dirtiness and incompleteness of the historical record, its multilingual cacophony and complexity? Anyone who portrays it differently is lying to you. Who is afraid of the bloody, rich mulch of life from which we all descend? Not any historian worth reading or listening to.

Well, nuts to that. Who demands that history be sanitized like that? Who is uncomfortable with the essential dirtiness and incompleteness of the historical record, its multilingual cacophony and complexity? Anyone who portrays it differently is lying to you. Who is afraid of the bloody, rich mulch of life from which we all descend? Not any historian worth reading or listening to.

I should have linked to these golden oldies in my original post, but eminent Latin@ scholar GayProf and I talked about this six years ago on both of our blogs:

Historiann and GayProf teach it all, Part I

Historiann and GayProf teach it all, Part II: how the west is (still) lost

Historiann and GayProf teach it all, Part III: Revolution!

LikeLike

Also note (as Piker observes in passing but doesn’t stop to engage with) two of Wood’s targets were essays published in the 2013 special issue of the WMQ on Atlantic Families – a project Sarah Pearsall, Karin Wulf and I facilitated and that you were also a great part of in the workshop that preceded it.

https://oieahc.wm.edu/wmq/Apr13/abstracts.html

I would like to have seen Piker do more with the implicit aversion to gender, family and sexuality as key sites for power relations and other issues in Wood’s choice of examples.

Great commentary as always from you here.

Julie Hardwick UT-Austin

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a great point, Julie–thanks for your comment. I noticed that Wood had picked on your guest-edited edition–I was at the conference at UT in 2011, as you may recall! I assume that that was in part Wood’s problem with that list of articles, at least as much as the geographi/ethnic/language issues that Piker raises.

LikeLike

(I mentioned in my comment you were a great part of the workshop iteration of that project! Sometimes you have to see being someone’s whipping horse as a triumph:-)

LikeLike

Absolutely!

And I should add: isn’t it shocking how little it takes to rile some people up? I mean, someone might mistake us for boring, middle-aged college professors, rather than the DANGEROUS RADICALS DESTROYING AMERICAN HISTORY we in fact aspire to be.

LikeLike

Even as a neophyte, who had never taken a course on Early America at any institution at any level, and was trying cautiously to read my way in, I never understood the mission of the WM 2ly as being limited to the “origins of the U. States.” Eating only on a picky basis like that is a good way to get skinny. Besides the awkward fact that Bailyn himself helped to turn the hounds loose on this one. What would be the point of putting an imaginary satellite in orbit somewhere over the North Atlantic if you weren’t going to interdict anything and everything that transcected your field of vision no matter where from or where bound? If it looks interesting, chase it, I say… What did Francis Drake have to do with the origins of the U. States,” besides everything? Piet Heyn?

LikeLike

YES to this: “Eating only on a picky basis like that is a good way to get skinny. Besides the awkward fact that Bailyn himself helped to turn the hounds loose on this one.” I thought the same thing too last winter when I first read Wood’s screed–Bailyn’s book seemed a miscast peg to hang his hat on.

Pre-deciding what’s interest and relevant is a poor way for a historian to procede. Also, it’s no fun. Boundary-policing is a fool’s errand; the people having fun are the boundary-crossers and those of us who are mixing it up and throwing it up on the wall. It won’t all stick, but good gravy: the rewards of this profession are so few and far-between for those of us who don’t have jobs at Brown or Harvard that we might as well have fun!

LikeLike

Gordon Wood reminds me of an old man standing on his porch shouting at the kids passing by on the sidewalk and telling them to stay off his lawn. The kids have never had any interest in being on his lawn and are headed to the 7-eleven for a slurpee. They have no idea what he is shouting about.

It reminds me a little bit of Richard Pipes and the other Sovietologists who came down like a ton of bricks on scholars like Sheila Fitzpatrick who decided it was time to do a social history of the Stalin era. Pipes and others went so far as to call Fitzpatrick a Stalinist in print, because she dared to show that the 1930s was an era of social mobility in the USSR, not just an era of terror. Even worse she actually delved into the messy business of collectivization and its social history. In the eyes of the Cold Warriors this was tantamount to an endorsement of the Soviet system. (Pipes was a Regan adviser on foreign policy and the Soviet Union in addition to being a historian of note. He was also part of Team B which was supposed to conduct an outside review of USSR’s capabilities, because the CIA’s Soviet analysts were supposedly a bunch of com-symp Liberals. Pretty much all of Team B’s prognostications were later proven wrong or inflated, but whatever.) Fitzpatrick has written a half dozen books since then. Her history of the Russian Revolution is one of the best short introductions for undergraduates I have ever read. Richard Pipes hasn’t written anything of note since the 1990s, except to rehash his arguments that the commies were bad. Social history is a mainstay of Soviet and Russian history and has reinvigorated political history.

The early American history parade is passing Gordon Wood by. There will always be a market for the herofication of the American Revolution, but it no longer has a monopoly. So enjoy the slurpee and walk the long way to the 7-eleven so you don’t have to listen to the scary old dude’s shouting.

LikeLike

Thanks, Matt, for that review of similar controversies in your field. I haven’t heard the name Richard Pipes since at least the early 1990s–but everyone knows who Sheila Fitzpatrick is. I’m glad to hear your recommendation of her take on the Russian Rev. I have to confess that it’s something I never really “got,” efforts to study the American, French, and Russian Revolutions in comparative perspective notwithstanding.

LikeLike

Thank you for Pigpen! Of course messy stories are more interesting! I’ve just weighed in on my alma mater’s discussion of how to deal with the legacy of Woodrow Wilson, and I said, this seems to me an example of a complicated story (because lots of Wilson as college president was very good, though much of Wilson as US President was very bad). And that the purpose of education was to help people deal with complicated stories.

LikeLike

Amen. I, too, loved the final metaphor (and the whole argument), and especially appreciated Pigpen as an illustration. (And I need to catch up with the Wilson debate).

LikeLike

Yes–and apparently, students at Oxford U. are now agitating for the removal of Cecil Rhodes’s statue at Oriel College.

LikeLike