I’m not a traditional historian. I don’t give a fig about chronology except (maybe) in my “first half” (1492-1877) of the U.S. History survey class, and I never care about “coverage.” Maybe it’s my short attention span, but I go for books and ideas that intrigue me rather than the idea that I need to “cover” certain decades or themes in my classes. The only kind of coverage I ever worry about is ensuring that my students are reading, hearing, and talking about as many different Americans as possible. I try to ensure that we are reading and talking about women and men alike, and Americans of all classes and ethnic backgrounds.

More proof that I’m probably a bad professor: I write syllabi for the courses I wish I could have taken. Selfish? Guilty as charged. But then I figure if I’m bored, how can my students not be bored too? I’m just not that good of an actor. Also, I’ve found that if it excites me (environmental history! material culture!), it’s probably going to interest the students more than a lecture or book I feel merely obligated to share with them.

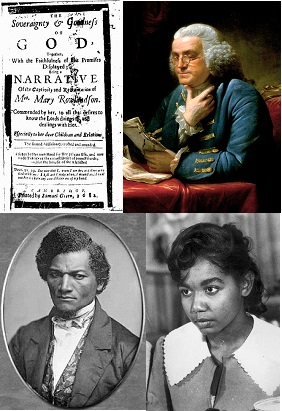

Joseph Adelman has an interesting blog post over at The Junto about teaching a history course organized around four American autobiographies rather than rigid notions of “coverage” and chronology. In a seminar for first-year students, I can see how it might be disorienting for them to jump from the 1670s (Mary Rowlandson) to the eighteenth century (Benjamin Franklin), and then to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with two African American autobiographies, Frederick Douglass and Melba Pattillo Beals. (He very generously provides a link to his syllabus, too.)

Adelman writes, “Both the students and I felt like we were missing something by not ever discussing the American Revolution, but for different reasons.” I would argue that his choice of books minimized the importance of the American Revolution, so maybe skipping it this time makes sense. After all, for three out of four of the people his students were reading about last semester, the ultimately conservative (if not revanchist!) revolution for home rule would have changed little if they were alive in the late eighteenth century. The Revolution only began the process of emancipation for some enslaved people in a very limited region, and in fact accelerated the mass disenfranchisement and enslavement of millions with the expansion of the U.S. empire in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Free women’s rights were debated and discussed, but the one state Constitution that permitted women to vote after independence was declared (New Jersey) revoked that right shortly after the turn of the nineteenth century.

Let’s review, with the help of a soupçon–just a suspicion–of chronology over the longue durée of American history: Voting rights for women in the U.S. weren’t realized until nearly 150 years after the American Revolution, and civil rights for African Americans weren’t even begun to be addressed until nearly 200 years after the Stamp Act crisis (in the 1964 Civil Rights and 1965 Voting Rights Acts.) Fifty years later, amidst an epidemic of executions of young black men, women, and even children, many of us today wonder, after Douglass, what is the Fourth of July to an eleven year-old African American boy playing in a park with a toy gun, or to a seventeen year-old young man walking home from a convenience store with a bag of Skittles?

I’m not suggesting that that Revolution was entirely irrelevant to the ultimate successes of the emancipation, and our ongoing struggles for women’s rights, gender and sexual equality, antiracism, and civil rights–all successful rights movements in American history argue effectively that their cause is in line with the values and ideals that propelled the American Revolution. (Witness the success recently of marriage equality versus traditional marriage–most Americans now see marriage and family relations as something that’s essential to liberty and equality. Few of us buy the notion that being American means telling other people who they may or may not marry.) But that’s because successful rights movements repurpose the language and ideals of the Revolution to suit their causes, not because those rights movements are somehow natural or logical outcomes of the Revolution itself. If the arc of history bends toward justice, it’s because there are a lot of people pulling hard in that direction in the here and now.

I like the solution to any chronology anxieties that either instructors or students might feel from commenter History Underfoot: “To get around the discomfort of not having chronology as the foundation, [one instructor] recommended the students create their own timeline, dropping in information as they learned it, sort of like a puzzle.” In fact, I’m going to suggest to my students that they do this too. Although I’m not big on chronology myself, timelines are a simple but highly useful DIY learning tool.

FWIW, as a student I really wanted context, and a sense of how everything “fit,” and I was much happier once I’d studied enough to be able to see connections–oh! this writer was influenced by that other guy, and this genre grew out of that one! Some of this was probably just me. . . but I also think that a mania for categorizing may be more typical of more junior and inexperienced learners who are looking for “answers.”

Remembering my own preferences, when I was first teaching, I tried to give A LOT of chronology and historical context; probably more than the average English professor. But now I realize that students really aren’t going to be able to put everything together and see patterns until they, too, have read and studied widely and deeply–and I want to encourage their own drawing of connections, according to what interests them. And I no longer want to put a little bit of everything on my survey syllabi; I’d rather teach 5-6 texts in depth than 20 in fragments.

I think I’m also more confident in my ability to just drop historical/period knowledge on a class when asked, on the fly, and so don’t have to build it in explicitly.

LikeLike

Oh, nostalgia — the first time I had to teach survey up through the Civil War, I was a grad student teaching summer school manymanymany years ago and trying to figure out how to do it in six weeks. I structured the course around several ideas that we were always looping back to and moving through more or less chronologically: expansion, opportunity (I always forget the third — migration, I think), and slavery became the unofficial fourth theme. Because some students were anxious about not getting Dates And Facts, I created a detailed handout for each session with key points/dates/facts. I loved it, because the terms were flexible enough that we could talk about what it was like to migrate voluntarily vs. involuntarily, what it was like to have opportunity and what it was like to *be* opportunity, how the Trail of Tears was about forcibly migrating some people to empty land so that one set of people could HAVE opportunity and others could be forcibly migrated in as PART of the opportunity. We read lots of primary sources, and we looped back to the themes all the time, and it worked out really well — students who needed more traditional stuff liked the handouts, and the students who needed something different (like, er, myself) enjoyed it. At the end of the six weeks, before the final, I did a review session where we tracked all of the themes chronologically. I’ve never had that kind of time since to try something like that again.

I think the six-weeks structure made it easier to try this, because coverage was so difficult for such a short class anyway that I knew some things would get left out no matter what I did.

LikeLike

Flavia’s introduction of context in place of chronology is important. The need for context is universal, both for understanding and for learning. People are not good at remembering random things but are good at remembering ordered things (so long as the order or ordering process is familiar–by which I mean they know and understand the context). Perhaps chronological presentations of history content are common because it’s an easy context. In the western scheme, time flies like an arrow. Other knowledge systems may use other ordering schemes (landscape features, for example), in which case teaching would be structured differently.

LikeLike

Our 11th grade US history course is entirely thematic, and has been for probably 8-9 years now. We use some chronology within the themes, but thematic is the key. In the last couple of years, we added a very brief 1-week unit at the start of the course to set up periodization in US history and have them create timelines that they can return to throughout the year. It works pretty well; I’m a big fan of the approach.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments, everyone–I was pulled offline yesterday afternoon & so wasn’t able to follow the conversation here closely. Yes, context is important–but in my view, students can figure out a lot of chronology on their own, as Tanya’s example shows.

Dates and chronology are like words in literature–you need to understand them, but they’re not the main point of studying a subject at the u/grad or graduate levels. And if students need to remediate, they can look it up on the Google or in a textbook or a dictionary.

LikeLike

(Isn’t anyone going to disagree with me??)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I won’t disagree with you personally, but institutional imperatives often *force* one into coverage, both chronologically and with regard to specific topics (i.e. Hirsch’s *Cultural Literacy*). Otherwise I’m 100 percent with you that the instructor MUST be interested in the content and format, or else that all-important chili-pepper-earning enthusiasm won’t shine. 😉

LikeLike

Thanks for the shout-out. I would love to hear how the DIY timelines work with your students. I have found they start out slow, but once they are filled in over time, it’s exciting for the students to see connections between different people/themes/events on their own. Great post.

LikeLike

Thanks! And thanks for sharing that great idea.

LikeLike

I like the syllabus and the idea of uncoverage in general. Joseph Adelman’s course on American biography looks great. I think his text focused approach is especially fruitful if you want to emphasize History as a discipline in the humanities, instead of it being slotted into the social sciences like it has been at our school since the 1960s.

Unfortunately as someone who teaches a subject other than US History it also turns me into the little green eyed monster. I wish I could articulate a critique of the approach that both engaged with the principles of uncoverage and thematic approaches, but without whinging about the privileged position of American history in the curriculum of higher ed. But let me try.

The problem I have is that I am not be able to use this model to teach modern central and eastern Europe. There are not enough primary sources translated into English to teach this way. I do not think I could find four autobiographies translated into English which covered the period from 1500 to the present from Warsaw to Constantinople. Even if I wanted to narrow the time period, it would be tough to find adequate sources. For example, there are some OK primary source materials for the nineteenth century, and some really great primary source collections about Central and Eastern Europe from 1945 to 1989. But there is almost nothing for the interwar period, while the best primary sources for the early 1900s are limited to intellectual history. Sometimes putting together a course that emphasizes primary sources in the standard chronological format can be a challenge. No matter how I organize the course, I end up leaning more on secondary materials than I would like.

Plus, students are not familiar with the chronological narrative of the Habsburg, Ottoman and Romanov empires. For example, I have plenty of smart students who think that Peter the Great and Catherine the Great were contemporaries rather than the bookends to the Russian history of the eighteenth century. When I teach my upper division history of Russia in the twentieth century, we spend the first five to six weeks doing the chronology and narrative of Russian History since the Time of Troubles to the present day. Then they take an old-fashioned blue book exam. We spend the remaining ten weeks of the semester addressing four thematic units ranging from the Russian Revolution to Chechnya. That is as close as I can get to “uncoverage.”

We might be able to change some of this by shifting the focus of what counts as scholarly work in the field. For example, there would be better teaching materials if historians of Central and Eastern Europe valued editing and translating primary sources as much as they value original research published as monographs and scholarly articles. One of the most impressive works in Russian History is Seventeen Moments in Soviet History http://soviethistory.msu.edu/. It was put together by James van Geldern, Lewis Siegelbaum, and Amy Nelson. There was another project led by Holly Case at Cornell, devoted to building a similar collection for Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe going back to 1500 but it folded after the foundation funding the site ran out. Even the Seventeen Moments site hangs on a tenuous thread. It was hacked and the site taken down in January 2015 and it did not return until last fall. From what I understand there were issues with funding and hosting the website.

Anyhow, congratulations to Joseph Adelman for putting together an outstanding course. Your colleagues who teach other histories in other geographies would like to do the same and wish you good luck in your endeavors. Historians of the US, when you are evaluating colleagues for tenure and mentoring junior faculty who don’t teach and research US History help us out by promoting the less prestigious work of translating and curating primary sources. Try to be understanding when we resort to old fashioned narrative histories to teach our students the basics of our regions and time periods.

LikeLike

I was thinking of people like you, Matt, when I wrote this post–it IS a luxury of American historians to assume that most of our students in U.S. universities will have had exposure to some of the basic facts and chronology of American history.

I think you make a great point about recognizing at T&P time the labor involved in effectively making up your own documents readers and translating other sources for your students. It’s something that most U.S. historians will never have to do, because most of us are monolingual and/or work exclusively in with an English-language historiography and primary sources as well.

LikeLike

I am teaching our undergraduate historiography and research methods class this year. In the fall semester I taught it with an emphasis on historiography as it has developed in the anglophone world, so I used a textbook written by a Brit, John Tosh, _The Pursuit of History_ and a historiography reader compiled by two New Zealanders Anna Green & Kathleen Troup, _The Houses of History_. Since Historiography is a required course for our Social Science History Teaching majors I also had the class read Marc Ferro’s _The Use and Abuse of History_ about how primary school children are taught history around the world.

The students really struggled with the readings for most the semester, but especially with Ferro. The Green and Troup book is really written for students in an introductory grad school class, so it probably went over the heads of two thirds of my students. But a large part of the problem was that the students had not read enough history about other parts of the world besides North America. They just don’t have the chronology and narrative to follow what is going on in Persian and Turkish history, or even Europe and Asia before 1800. They have a hard time slotting new materials and chronologies into their existing knowledge.

This semester I dropped all three books in favor of Caroline Hoefferle’s _The Essential Historiography Reader_. I like the book so far, but our first class discussion is today, so we’ll see how it goes. One feature that made me decide on Hoefferle is that every chapter has at least one sample author writing about the American Revolution. I figured that this was one part of history all the students would know fairly well and that they could then focus their critical attention on the argument and sources of the author, rather than trying to understand the narrative.

LikeLike

I took such a thematic course (in art history) as an undergrad, when the department had decided to jettison the traditional, chronological survey for very excellent intellectual reasons. It was fantastic. For those who had already taken a chronological survey in high school or college, whether in history or art history. The rest were just lost. It may have been the proffies and the fact that it was the first iteration of this new approach, but it seemed to work best for those of us who had some sense of the canon that was being busted. In any event, the department eventually abandoned this approach and returned to the survey.

LikeLike

Which is not to say that the course described is without chronology, but just that students, who likely expect history courses to be chronological, may need a lot of help to navigate one in which straightforward chronology is not the primary structuring framework.

LikeLike

I definitely agree with this, and that’s why I tried to incorporate some of that structure into my (very old) class with handouts. My own undergraduate survey course had been thematic and since I had gone to a very weak high school, I was kind of lost, though at some point about halfway through I figured out what was going on with the themes and was able to use that to learn how to read and respond to the professor’s questions. I still felt the absence of having some real “narrative” chronological structure. I think the fact that I myself had to sort out the chronological stuff in grad school (my program’s chronological historiographical sequence of US history courses was a godsend to me) made me think about trying to do both at once.

LikeLike

Thanks for extending the conversation here, Historiann. I’ve enjoyed reading the comments here as well as over at the Junto. Like Tim Lacy, I won’t disagree with you really (though I second his notion of requirements for coverage).

But I would say that my post reveals in an indirect way that I am someone more inclined towards chronology as an organizing factor in both my teaching and my research, even when working thematically. Perhaps that’s inherent, perhaps it’s because my original starting point for entering the field was political history, which is a bit more chronological in focus.

In any case, your post has me thinking that the next step is to re-engineer my survey syllabus when I next teach it (after this semester, of course) to rethink the relationship of themes, chronology, and coverage. There are a number of imperatives built into the survey course that may make that process challenging — it serves not only as a gen ed, but also as a gateway to the major and as a requirement for education majors who are required to study the U.S. and Massachusetts constitutions and to earn teaching competency in a heavily New England-flavored version of American history. But teaching the autobiographies course and reading your post (and the other comments this week) has me thinking far more seriously about the tyranny of chronology in the survey as well.

LikeLike

I think chronology is much more important in traditional political and economic history, for example, because you’re looking at a rapid rate of change over the past 250-300 years or so. When looking at questions of race, ethnicity, gender, and violence–as you did last semester in your American autobiography course–then the rate of change is not nearly as rapid nor the direction of change so clear at all times.

Welcome to the world of the anti-Whig (non-Whig? post-Whig?) historians! It’s more interesting, but it’s never as reassuring as a Whig narrative.

LikeLike

I don’t know what else it may say about me, but I tend to think of my survey as having more of a declension narrative than a Whig one…

LikeLike

HAHahaha! And *my* survey probably does have a Whiggish feel, although I try to work against it.

I frequently ask students to think about things like race, violence, or gender across 3 centuries, so that mostly works to emphasize continuity rather than change.

LikeLike

I have long wanted to reorganize my medieval survey this way. Once I’ve got this stupid paper nailed down, I’m going to check this out.

LikeLike

I have long taught this way. As a medievalist teaching on a quarter system, uchronia is my only choice. Even if I split the Middle Ages into 2 halves, it still isn’t viable to do a chronological course covering 100-1500 of the whole of Europe + parts of the Middle East (Crusades).

I tend to arrange my materials in chronological order, but to narrow my focus by theme. Medieval sex/gender/sexualities; tracing particular religious formations as a strand, picked out through a long span of time; or particular processes like conversion. It is much easier to teach them how to think like historians when offering a focussed set of readings or issues, than trying to cover everything for a continent for several centuries. I suspect the chronology approach works far better for modernists, and/or for people teaching on a semester system.

LikeLike

So, I’m currently teaching the second half of world history (the world since 1500). The only good thing is that you know you wont cover everything! I told my students today that we would move between the 50,000 foot view of big patterns and themes, and then go down to land and see what’s happening on the ground.

My experiment this year is that one assignment will be a class timeline: working in teams, they will write four entries (at least one biographical, one on event/movement, and one on art/material culture) and each discussion section will have a geogrpahical region for each period… and all the IDs for the exam will come from the timeline. My goal for this is two-fold: first, to have some writing which is more outward facing than the usual history paper; second, to remind them of the importance of sequence. Dates are not that important, but what comes before what is. I will report on this at the end of the semester!

LikeLike

That’s a great way to put it, Susan: sequence, not dates. I like that! (Although in teaching world history, even sequence is complicated by the fact that different cultures/regions are dealing with different issues at different times in history, even in the “modern” world post-1500. Or especially in the “modern” world, I should say.

LikeLike

Susan, this sounds like a terrific assignment and I am going to borrow it for my western civ survey courses. Right now I have the students create the chronology question for the midterm and the final. It is based on the same principle of students knowing the sequence of events rather than the dates. I like your idea of turning it into a timeline with different types of entries (biography, event, and art) and definitions. That really gets to the historical significance piece of the question. Why do these people, events or things count, why not others instead? What makes them significant in the story we are trying to tell?

LikeLike

Matt, there are some good and free things you can use for this. . . but you might want to wait to see the result!

LikeLike

Great thoughts and conversation! I don’t remember any of my undergrad history courses being taught in this way but it seems like a really cool way to structure a course if one wants students to starting learning how to think like a historian. And thought-provoking as I try to think about how to structure survey-type geology courses to do the same sort of thing: not just memorize facts/chronology but to learn the process of doing geology science.

LikeLike

OMG. I can’t even grasp geological time, let alone teaching it. My hat is off to you, ESP.

LikeLike

Like EarthSciProf, teaching American environmental history has pushed me into a compromise of sorts. The first half of the class is more-or-less chronological, beginning in Africa with the rise of H. sapiens and concluding around the beginning of the 20th c. Then we switch to themes, and talk about water, mining, agriculture, energy, climate change, etc. in the second half, which allows me to take the course all the way to the present.

This seems to work for the students. It did raise objections from an editor, when I pitched the textbook. I had to choose, I was told, between chronology and theme. The editor clearly preferred theme, but I really didn’t want to give up on talking about what actually happened with students (non-history majors) who I find often don’t have much accurate knowledge of American history.

LikeLike

Whoa–that some deep history there!

I can understand the editor’s caution–unless you know there are others teaching like you, I’m sure she or he worried about whether they could make bank with a book like that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re probably right. In the end I decided to self-publish it rather than choose a format that didn’t make sense for my class and resubmit my proposal. So now it’s an experiment with a low front-end cost.

LikeLike

I think that’s the way to go in terms of your current teaching needs, but what about recruiting some colleagues to your scheme via a website or a blog? Publishers might be interested in pursuing the book with you if you can show them that there’s a constituency out there who are eager for your course materials & ideas, and that they will assign your book.

At the very least, it would be a service to the profession, and it could be a fun little soapbox for you. (Lord knows that my blog is mostly my little soapbox/sandbox, and it’s still keeps me entertained. . . )

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, the blog thing is fun. Also, http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/161641?platform=hootsuite

LikeLike