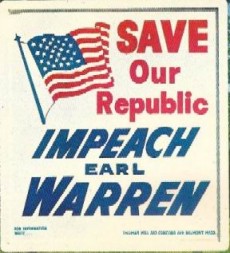

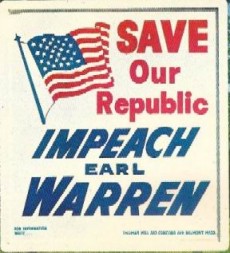

Drop whatever you’re doing now and go read Randall Balmer’s excellent article on “The Real Origins of the Religious Right.” Subtitle: “They’ll tell you it was abortion. Sorry, the historical record is clear: it was segregation.” Balmer, who has just published Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter, recounts what he found in the archives while researching that book. If it really was Roe that radicalized the Christian right, then what the hell were all of those “Impeach Earl Warren” bumper stickers and billboards about in the 1950s, 60s and 70s? (Isn’t that a nice touch with the stars and bars over there on the left? Very subtle.)

That’s right, friends: it was Brown v. Board of Education, not Roe:

This myth of origins is oft repeated by the movement’s leaders. In his 2005 book, Jerry Falwell, the firebrand fundamentalist preacher, recounts his distress upon reading about the ruling in the Jan. 23, 1973, edition of the Lynchburg News: “I sat there staring at the Roe v. Wade story,” Falwell writes, “growing more and more fearful of the consequences of the Supreme Court’s act and wondering why so few voices had been raised against it.” Evangelicals, he decided, needed to organize.

Some of these anti-Roe crusaders even went so far as to call themselves “new abolitionists,” invoking their antebellum predecessors who had fought to eradicate slavery.

But the abortion myth quickly collapses under historical scrutiny. In fact, it wasn’t until 1979—a full six years after Roe—that evangelical leaders, at the behest of conservative activist Paul Weyrich, seized on abortion not for moral reasons, but as a rallying-cry to deny President Jimmy Carter a second term. Why? Because the anti-abortion crusade was more palatable than the religious right’s real motive: protecting segregated schools. So much for the new abolitionism.

I’m so happy to have found Balmer’s historical analysis, because I’ve been dubious all along about the legend of how

Roe v. Wade mobilized a generation of Protestant Christians. He reminds us that abortion was considered “a Catholic issue,” not an evangelical Protestant issue. In fact

:

When the Roe decision was handed down, W. A. Criswell, the Southern Baptist Convention’s former president and pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas—also one of the most famous fundamentalists of the 20th century—was pleased: “I have always felt that it was only after a child was born and had a life separate from its mother that it became an individual person,” he said, “and it has always, therefore, seemed to me that what is best for the mother and for the future should be allowed.”

Isn’t this exactly what the new President of the Organization of American Historians, Patricia Limerick of the University of Colorado, wrote about in her recent plea,

“Professors, I Need Your Help?”, her belated call to answer

Nicholas Kristof’s claim that “most” scholars “just don’t matter in today’s great debates.” Limerick writes,

Public historians, do not race to your laptops! I am very aware of your important roles in the world, and with a year as OAH President, I will get to celebrating you soon. But Kristof’s column took aim at professors, and indeed, the caricature of academics who do not venture out of their ivory towers burdens us with our weakest flank.

If you are a historian based in academia and also engaged in the world beyond the borders of your campus, please write me. Tell me who you are, what your field is, what you teach, what you write about, and what sort of activity—working with K–12 teachers, giving public lectures, participating in the design of museum exhibits, advising nonprofits, talking to reporters, writing op-ed pieces or blogs, etc.—you engage in outside your university or college. If you involve your students in these enterprises, all the better—please let me know about how you may have, for instance, hitched up the writing and research assignments in your class to the public benefit.

So, there you go. I nominate Randall Balmer as a publicly engaged historian who can write for general audiences and offer genuinely useful information. I also urge the rest of you to take up Limerick’s call. I’ll write to her to let her know about this blog, too–I’ve been critical of her in the past (over her decision to support a conservative pol for President of her uni), but that’s public engagement, ain’t it? You can contact her at historians AT centerwest DOT org.

(I was surprised to see that Limerick isn’t on Twitter. Her Center for the American West has a Twitter account. Pro tip to Professor Limerick: get on Twitter. It’s where the kids are, and it will immediately connect you to loads of historians who are very junior and/or have not yet found permanent jobs. That is, it’s not just “professors” and public historians who are engaged in useful public outreach!)

I was surprised to see that the “Impeach Earl Warren” committee wasn’t on Twitter; until I realized, oh, yeah, they couldn’t have been. What jumped out of that picture even more than the tail-fins on the cars was the P.O. Box… where it should have said http://www.com. I pulled a paper out of a box at the bottom of the closet recently that I wrote about twenty-five years ago and sort of couldn’t fathom that I could have found anything without being able to resort to all of the electronic tools that we just take for granted today. In that context, the paper didn’t actually seem all that bad.

I wonder what constituted whatever the then-equivalent of “viral” would have been in the imaginations of the people tearing open envelopes back at P.O. Box 1387? If you add up the letters, numbers, spaces, punctuations, and individual stars and stripes, and factored in the speed of those cars, that lonely billboard would have just about qualified for an Eisenhower-era tweet!

LikeLike

The newly found origin of the Christian Right is valid only until someone finds an even earlier starting point. Segregation is probably crucial, but Southern nationalism and strong support for the rich are also probably important.

Kristof’s and his likes proclamations shouldn’t affect anyone. Did they ask plumbers to be more involved? How about physicians? Bottom feeders see the world from below; that isn’t the view everyone else has nor is it the majority view. Sharks ignore bottom feeders; we should too.

LikeLike

The one reason abortion and uppity women only drove them nuts later is because before then women weren’t even on the map. And don’t forget Communism aka uppity workers. The John Birchers were a big deal well before Brown v BofE. Although the KKK predated them all so, ultimately, yes, fear of that particular Other came up early on the radar of the god-fearing Right.

But let’s face it. There’s some 30% of the population who seems to need someone to hate. The specific group(s) targeted varies, but the need for therapy among the 30% does not.

LikeLike

I agree with you that I’m glad someone is exploding the myth that it was a widespread and immediate anti-abortion spirit that moved American evangelicals into politics. I remember the years after Roe v. Wade as little exercised by the question of abortion, much more moral outrage being thrown at the ERA, for instance. That quotation from Criswell is amazing. Great engaged history, you’re right!

LikeLike

Just love that this messes up a narrative. As quixote suggests, however, it also connects to anti-communism. I was at a conference once where Eric Hobsbawm commented that almost all inter-racial couples in the late 40s/early 50s were communists. (This was at a session on the Scottsboro boys.) I’m sure he’s talking about those in the intelligentsia (that’s where Hobsbawm lived) but still. One of the problems with the communists was that they didn’t play by the racial rules.

LikeLike

Interracial couples? I’m sure there were many in that era, despite the laws in the South. And that a lot of them were roughly similar to Richard and Mildred Loving. Average people don’t tend to become famous if their case doesn’t end up in front of the Supreme Court. And, as Susan says, Eric Hobsbawm wouldn’t have known many average people.

Broader point, though: isn’t it finally time to get rid of this idea that the only possible reasons to be anti-Communist are a)fear of uppity workers or b)racism??I just finished Thomas Devine’s history of Henry Wallace’s 1948 presidential campaign. One of the major reasons the campaign failed, according to the book, was that it became increasingly obvious that the Communists were running the show. A lot of Wallace’s speeches looked like Communist talking points, etc. This put off a lot of people who were mere “progressives”. It also wasn’t terribly convincing to argue in 1948 that the Soviet Union had absolutely zero aggressive intentions. “Progressives” should ponder this sort of thing.

LikeLike

I have to agree with some of the other commentators that this article seems a bit off. Not that segregation wasn’t a major issue for a lot of the Christian Right, but it seems more like correlation than causation (a lot of evangelical Christians were segregationists, but that doesn’t mean that segregation led to the Christian Right as a political force). “Your political movement has its roots in racism” is definitely a good political attack, but not necessarily good history.

I thought Balmer’s article completely ignored theology, as well as other important sources of Christian right politics, from anti-communism to anti-New Deal sentiment. Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors and its coverage of the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade jumps immediately to mind, as well as works by Jeffrey Carpenter, Darren Dochuk, and parts of Kim Phillips-Fein’s Invisible Hands.

Overall, it just seems questionable to place all of the credit/blame for the rise of the Christian Right on segregation—instead of abortion. Especially because opposition to segregation was such a central part of the rise of the non-Evangelical right. It seems much more honest (and politically useful) to understand the modern Christian Right not as monolithic as the complex result of a variety of forces, including racism.

LikeLike

I didn’t see Balmer as making an argument in his full article that desegregation was the prime or sole motivation of the Right. I think he was trying to correct the record for a movement that dates its mobilization to 1973, rather than 1954 (Brown) or 1970 (the Green decision of which he writes). After all, his article uses mostly evidence from the 1970s, presumably collected while researching his book on Jimmy Carter.

I’m sure there are loads of Christian Right-wingers these days who are honestly anti-abortion and honestly don’t see themselves as racist or affiliated with a movement whose modern origins are in Brown & Green rather than Roe. Balmer’s effort to decouple the rise of the modern right from Roe is necessary and important.

LikeLike