I began my career at Penn State and spent seven years there, getting tenure, before I moved on. It’s been awful to watch the events of the last month play out.

Most of the commentary about the child sex abuse allegations against the former football coach and the administrative failure to stop it have focused on the corrupting influence of football — on the health and safety of women and children; on academic affairs; on the budget as a whole. These critiques are important.

But I never had a lot of contact with the football program. No football player ever enrolled in one of my classes, but perhaps that was because of the courses I taught, which are about gender and poverty. (Not so popular with male athletes?) Football wasn’t a world I knew well.

I did, however, have contact with the university administration, and the way I see it, it deserves more attention in the analysis of what went wrong at Penn State.

The administration is incredibly powerful at Penn State. I’m certainly not the first person to note that. While I was there it was a constant subject of discussion among the faculty. As so many of them observed over the years, the Penn State administration is deeply hierarchical, a thoroughly top-down affair. From my perspective as a new faculty member, the signature feature was the department head system, rather than a chair system. Chairs are elected by and represent the faculty in their departments. Heads are hired by the deans and are responsible, strictly speaking, to them alone; they serve at the pleasure of the dean. Department heads are thus arms of the administration and departments are its functional appendages.

The head system symbolized the way power works at Penn State. It is highly centralized and concentrated in relatively few hands. So, too, is decision making. The faculty senate at Penn State holds no real authority. Faculty members are rarely consulted and have relatively little influence. Staff members hold no power, either. They are not unionized. And the geographic location of Penn State in the center of an enormous and depressed former industrial region means that the university is the only game in town. Few on staff are in a position to challenge power.

From what I saw as a junior professor, the powerful, hierarchical administration produced some questionable outcomes: a department head dismissed with minimal procedure; hires that did not meet my professional organization’s standard practices for searches; and excessive administrative control over general research agendas (several journalists have alleged this regarding Penn State’s close connection to the natural gas companies and its generous support of research ok’ing the controversial practice of “fracking”).

What happened when the Penn State administration, including the President, failed to act to stop sex crimes against children was indicative of a lot of other less horrifying failures, too. In a place where there is little policy, procedure, or culture to encourage consultation or shared decision-making, bad things can happen – to students, faculty, staff, or the public. None of it is good for the university as a whole.

There are so many good people on the faculty and staff at Penn State who want to participate and have tried to dent the walls of power. And their greater participation would undoubtedly make a difference. As Penn State English professor, Michael Berube, pointed out in the New York Times, it’s hard to believe that the alleged crimes of the assistant football coach would have been covered up by, say, the faculty senate, if it had been consulted.

I know that Penn State is not unique in its hierarchical administration. Many other universities already follow Penn State’s model or are heading in that direction. But the alleged crimes and cover up at Penn State should give them pause.

Historiann again here: I don’t have anything to add, except to observe that the more I hear about “Happy Valley,” the more it sounds like a cult. Why do people fall into it? What do non-athletes and “fans” get out of the mass delusion that football should be a big part of their lives? Why do university administrators feed this delusion?

And finally, why am I ultimately unsurprised to hear that football culture and authoritarian management style go hand-in-hand?

“I know that Penn State is not unique in its hierarchical administration. Many other universities already follow Penn State’s model or are heading in that direction.” Indeed.

Furthermore, head or chair is coin toss in many universities as well. At my U, we have both. My local experience is that a head doesn’t wield more power than a chair; the head’s power is a reflection of the faculty’s willingness to cooperate.

Higher ups seldom consults down. I hear the same from way too many. It really doesn’t matter whether it’s a school or a large company. The modern flat organizations are infrequently applied to the government, school and other organizations. Although we have known that flat organization are superior to hierarchical ones for decades, there few buyers. (They love the military as in “yes, sir; no sir”).

Cover ups and willing to hide dirty laundry is a function of the organizational size and the societal tendency. We accept torture for the good of the country (according to some). Why not except sexual abuse for the good of the university?

LikeLike

Medical school department chairs are appointed by the dean. However, because of the way that medical school finances are structured–with the overwhelmingly vast majority of revenue generated directly by the faculty from research grants and clinical fees–the faculty actually have a lot of power, even on an individual basis, grounded in the prospect that they might take their grants and clinical fees elsewhere. Therefore, department chairs are not generally appointed over objections of departmental faculty, and the decision-making at the departmental level is generally quite democratic.

LikeLike

I wonder if the nature of hiearchial institutions feeds this sort of thing, because the problem is always fed up the way, and never horizontally. So if there is a ‘discipline’ problem, it gets pushed up to the next individual on the ladder, who in turn pushes it up. But, there is no procedure there for somebody to say ‘stop, it’s time to phone the police’- there is no policy for looking outside the structure. And, I think you see this at a long of very hiearchial institutions, not just universities, such as the child abuse scandals in the Catholic Church. Often people knew this went on and reported it, but nobody thought they should call the police. And, a lot of the new policy around stopping this happening again, has been educating people on when to call in outside help, and in getting institutions to recognise the difference between internal ‘discipline’ issues and crime.

Moreover in an interesting way, it’s like the ‘team-bonding’ part of football, which means team-players often act eggregiously as a group and then cover up for each other (even doing things that they would be repulsed about as individuals), is being played out at an institutional level. The group dynamic, where you only work within your own group’s regulatory mechanisms and fail to see that your group is part of the wider world which may have different standards, is not just happening in the changing room, but in the institution as a whole.

LikeLike

We have elected chairs, not appointed department “heads,” but no faculty senate, rather a “university” senate, which while it has a clear faculty majority, also has significant membership of administrators and even a body of seats allocated to student representatives. It functions pretty much like your basic high school student council, with a lot of “what shape and color should the new trash cans on the quadrangle be,” although there is also a lot of process-intensive intrusiveness on curricular issues that I think ought not to be there. I suppose it’s all very hippy-trippy (in a stakeholder inclusivity sort of a way), but the ad/min pretty much gets what it wants. In the one big curricular brouhaha of the last few years, the student “senators” actually came down on the right side, allying with most of the faculty, which threatened years and years of “work” by the types who like to do that sort of “work.” But the admins just waited them out, holding off on the vote until evening classes began, at which point the student “senators” began to peal off to do the work they actually paid to come here to do. Then the big “A” faction rammed through the “work” that they intended to see done all along (and that only after a botched vote count). So I think top-down comes in all shapes and sizes.

LikeLike

I taught at a branch of the Penn State system and it was the same way. Very hierarchical and very male. The misbehavior and abuse of women was rampant at the campus I was at. I left quickly and I knew women who left without having another job lined up because it was so bad. And it wasn’t just the administration. Male faculty AND students treated female faculty abysmally. Male faculty who treated their female colleagues with respect were shat upon too. It was a bad, bad place.

LikeLike

A recommendation, prompted by Historiann’s questions:

“The Stronger Women Get, The More Men Love Football: Sexism and the American Culture of Sports,” by Mariah Burton Nelson. It was written in 1994, but not much has changed (alas).

LikeLike

I also teach at a public university with the same model as Penn State’s. I had come from a far less authoritarian (public) university and was pretty shocked at how rigidly hierarchical and opaque my university is. Everything that happens administratively is shrouded in mystery, and there is little transparency anywhere (especially in the process of tenure and promotion). We also have a “head” instead of a “chair”. I don’t know how much covering up here happens re: the sports team (kind of a big deal, but not a huge deal), but I know for a fact that the university has an appalling reputation (even by terrible university standards) for covering up rape and sexual assault on female students. (And a former president who apparently engaged in all kinds of inappropriate sexual relationships in his office, or so I’ve heard. – before my time.) I completely agree w/ @Feminist Avatar’s points about the nature of hierarchical systems.

LikeLike

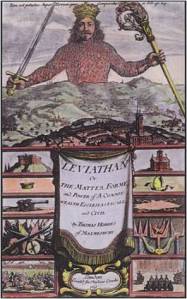

Apologies for the frivolous comment, but: the football Leviathan has seriously, seriously made my day. Many thanks!

LikeLike

I agree with what folks have said about the nature of hierarchy, but I want to add another anecdata point to Indyanna’s about the possibility for discrepancy between official institutional practices and de facto practices. My small, private, liberal arts-ish institution does _not_ have a faculty senate– we’re all officially part of the governance structure and all have a vote on everything– and we have a chair structure. However, because of the history of the institution and (to some degree) the personalities of individuals, those formal horizontal structures mean very little when it comes to decision- and policy- making.

All of this to say, it’s complicated. (And if anyone has strategies/recommendations for how a junior faculty member can challenge/disrupt this kind of power, I’d welcome them. Although I don’t want to hijack the blog.)

LikeLike

comparatrice: thanks! If only I had the time and the photoshop skills, I would have tried to replace the sword and the scepter with a football and a helmet.

Sensible: read Michael Zuckerman’s article on the “Social Context of Democracy in (18th C) Massachusetts,” 1968 WMQ, in which he analyzes a very similar-sounding political dynamic. I don’t know how a single junior faculty member could possibly disrupt power dynamics like that, but banding together with several other junior faculty might be a more effective (as well as a more prudent) way to go.

LikeLike

Just to add to the “it’s complicated” end of things, THE most authoritarian, hierarchical university I have worked in had no sports teams at all.

Our chairs are appointed by the Dean in consultation with the faculty. And it is kind of “who will do it/be conscientious, competent, and fair?”

LikeLike

I think it’s the case at most unis that Chairs serve at the pleasure of the Dean, although they are usually elected by their faculties first. At least, that’s how it works at Baa Ram U.–I’ve never heard of a Dean refusing to permit a Chair to serve as Chair, but she has the power to refuse to permit an elected Chair to serve. (And that’s how it was at the other places I’ve worked, too.)

LikeLike

I’ve never heard of a Dean refusing to permit a Chair to serve

That happened in my department once, many years ago. It was bigotry on the part of the dean.

LikeLike

If you report criminal acts to policy or law enforcement authorities, you may be protected by whistleblower statutes in your state. That’s the case in PA, so there’s no excuse for Paterno or McQueary not to have gone to the police — other than institutional capture, i.e. they were captured by the institution in which they worked. *Why* they were captured is probably the more interesting inquiry than the fact that they were captured.

The internal hierarchies are set up exactly to keep things in-house, to create institutional capture. That’s why there are private security forces at colleges and universities. That there’s no “system” set up, or “trigger” enabled for going outside the system is a feature, not a bug. That is why whistleblower statutes exist, because of that reality.

LikeLike

re: why people obsess over football, it’s dysfunctional fulfillment of the basic need to belong. Maslow put the need to belong to a group, to have friends, etc. on the third rung of his pyramid. However, Americans (moreso men than women) live in a culture that atomizes them. In general, we don’t have deep relationships with anyone besides our spouses. so Americans fulfill their relationship needs with sports fandom and fanatical religion.

LikeLike

It seems to me that understanding and, if not sympathizing, at least appreciating the importance of college football to non-athletes is the first step in relegating it to a lesser and more appropriate role, much less attempting to end it.

To me, it’s like failing to understand the cultural importance of 4-H to rural kids in the quest to call out the cooperative extension service as a publicly-subsidized mouthpiece for agribusiness conglomerates. It’s not that the latter isn’t true or that 4-H kids aren’t indoctrinated into Big Ag’s perspectives. But if you can’t understand and appreciate why 4-H is an important identity AND the only contact most of those communities will ever have with the state university that their taxes support, you’re probably doomed to fail.

Sports culture may end up as a dysfunctional fulfillment of the basic need to belong.

But, importantly, it’s not a fulfillment of a dysfunctional need to belong.

LikeLike

I agree. I just don’t worship at that church, and neither does anyone else in my immediate family.

I also don’t think that 4-H is nearly as corrosive of the intellectual and social life of universities as football is! (But I get that you weren’t making an exact comparison.)

LikeLike

In Scotland, where football (soccer) teams have religious affiliations and yet church attendance is declining, there has been some really nice analysis of the ways that football has replaced religion whilst still allowing people a religious identity. So, people no longer go to church on a Sunday, but instead go to a match, where they follow certain rituals, including worship (singing anthems), and because they follow a team with a particular religious identity, they can still be identified as ‘protestant’, ‘catholic’, etc.

I am not sure though whether ‘football’ is really the problem, as much as that we live in a deeply misogynist world, where the abuse and sexual exploitation of women and children is a central part of demonstrating power. So, that group bonding, particularly in male-only groups, is often reinforced through ‘othering’ and then abusing women. There is a quite a lot of work on the way that introducing even small numbers of women into male-only spaces can change the outcomes for women for the better. But, sports is one area, where gender segregation remains central to the structure. If such groups no longer acted badly, would mass support for such teams still be problematic?

LikeLike