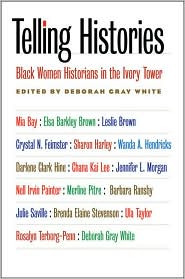

Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower, edited by Deborah Gray White, features autobiographical essays from prominent African American women historians that reflect on their careers, their tenure battles, and their struggles to invent the field of African American women’s history at the same time as they were forced to fight to make and preserve spaces for themselves within the historical profession. I blogged about this book briefly two years ago, but just this week finally sat down to read it. (Consider this my slight contribution to Women’s History Month blogging.)

Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower, edited by Deborah Gray White, features autobiographical essays from prominent African American women historians that reflect on their careers, their tenure battles, and their struggles to invent the field of African American women’s history at the same time as they were forced to fight to make and preserve spaces for themselves within the historical profession. I blogged about this book briefly two years ago, but just this week finally sat down to read it. (Consider this my slight contribution to Women’s History Month blogging.)

It is good to be reminded of how new the field of African American women’s history is–the contributors to this volume were born in the 1940s-1960s. They are people we know and work with, and they are truly a pioneer generation. White’s introductory essay does a brilliant job of highlighting the awesome challenges of professing black women’s history from inside a black woman’s body:

Educated African American women believed they had to overcome their history before they could do their history. Yet the nature of the history they sought to overcome was so embarassing and demeaning [of racial, class, and sexual exploitation and abuse] that it kept them from engaging that history in all but the most indirect manner. It was not by choice, therefore, but by necessity that we came late to the historical profession.

White and her contributors explain the many struggles that black women faced as they began to enter the profession in the 1960s and 1970s–the obligation placed on many to serve their communities rather than their intellectual ambitions; the scoffing and disbelief they faced in white and black male mentors who were mostly hostile to their interest in women’s history; the stresses of entering work environments in which the other people who look like them are all secretaries or janitorial staff; the racism and sexism of students who walk out of their classes and refuse to recognize their intellectual and professional authority; the cluelessness or plain old racism of overwhelmingly white feminist scholarly communities; and the never-ending suspicion of other historians that black women’s history can never be “objective” if it’s written by black women.

Because so many of the books by the authors in this collection have won prizes and have come to define the field they invented, those of us who are their peers or who are slightly younger take their success as natural, or foreordained. This collection makes it clear that every degree, every tenure-track job, every tenure decision, every book contract, every article, and every fellowship or prize was fought for, fought over, and only after overwhelming hard work, sacrifice, and protracted struggle were they won. White’s own book, Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South (1985; 1999) has since its publication 26 years ago been recognized as an original and excellent contribution to American history. It still remains a signal title in African American women’s history–which suggests both its quality, but also I think suggests that doing black women’s history is still really difficult both professionally and personally. These essays offer troubling and often disturbing evidence of how difficult those struggles have been for the contributors, even to the present day.

Enslaved women’s history I think remains an especially overlooked field, and yet enslaved women are everywhere in the primary sources I read–even sources in Northern New England history, which is not something I expected based on my knowledge of the secondary sources. I’m highly skeptical of anyone who says to anyone else, “It would be nice if you could write that history, but there are no sources.” Those of us who train graduate students should take a vow never to say that, ever, and instead to work with students to find ways of finding new sources or of reading old sources in fresh ways.

This book should be required reading for history graduate students and all historians. Think of it as companion to those venerable classics, Peter Novick’s That Noble Dream (1988) and Bonnie Smith’s The Gender of History (1998)–it’s kind of a nice coincidence that these titles are each separated by exactly a decade (1988, ’98, and 2008). This book is not just for black scholars or African American historians–it’s for everyone. Like I tell anyone who will listen to me, queer theory isn’t just for gay scholars or for historians of homosexuality–it’s good for everyone, because both queer theory and Telling Histories teach everyone to be alert to our assumptions about the way the world (or history) works, and they urge us to question those assumptions and to see the world from a different vantage. And how is that not good for historians, or for any scholars?

The “it would be nice” but “there are no sources” trope appears and reappears in some amazing contexts, some of them well short of being as distant from the canon as this one–and even sometimes from the mouths of scholars whose own prior work would suggest the opposite. One wonders whether it isn’t just some vestigial scholarly muscle that synapses irregularly? Or whether the enunciators of this point don’t conclude that they’d rather discourage a neophyte from a potentially rich topic rather than send one off the edge of the earth? That should certainly be a mainstay of doctoral-level mentoring, at least: “…. work with students to find ways of finding new sources…” Isn’t that where the real fun of scholarship begins? In the era of the internet, “there are no sources” just won’t fly. New questions, or just plain curiosity, and shoe leather, uncover new sources.

LikeLike

It seems to me that the “there are no sources” argument really means “I have no idea how to do this type of research.” There are always ways of wringing stories out of an archive, it just might require a different set of skills.

LikeLike

A related criticism of black women’s history that I have encountered to a disturbing extent is that it is only legitimate when black women are compared to other groups (white women, immigrants etc.). Writing a book that focuses solely on black women is often questioned (particularly by senior scholars in my department), while a book that focuses solely on say white men never faces such challenges. I am tempted at the next talk in my department that focuses on white men to ask, “Where are the black women? You can’t make these arguments without a comparison to them.” The silence and anger that would follow would be priceless.

LikeLike

Indyanna and GayProf: I’m glad you share my skepticism. I never fail to be impressed that after I’ve read an innovative new book on X or Q subject, I start seeing and thinking of all kinds of evidence for X or Q in the primary sources I know best. It’s all a matter of perspective. I’m thrilled that I get a chance to do some African American women’s history in the book I’m writing now, in large part because of the trailblazers who contributed to the volume under discussion.

widegon’s comment is telling of the state of the field now. I’m not surprised that black women are frequently seen as adjuncts to the “real” (male) African American and the “real” (white) women’s history. It’s like we can’t see or understand black women’s experiences unless they’re translated through an intermediate experience that they’ve already decided is legitimate (or legitimate enough, anyway.)

LikeLike

I read this book last year, when shit was hitting the fan in my graduate career, and it became evident to me that there was no other way to explain the discrepancy between the way I was being treated and the way my colleagues who had the same advisor were being treated other than the fact that ze had made all kinds of false assumptions about my work ethic, my intellectual curiosity, and where I was vis-a-vis my cohort based on nothing but my black skin.

The book was immensely useful, and yet frustrating in another way. I am not downplaying the struggles these women had trying to do Afam women’s history, but I really wanted to hear from black women who were working in fields other than Afam women’s history, and who didn’t even have the small cohort of crucial support that the women in this volume had managed to cultivate in their respective programs. In my experience, the subject I study isn’t questioned; it fits into the kind of scholarship that’s deemed acceptable. (I mean that in the broadest sense; I’m sure there are those who would argue on the nitty gritty of my work.) But my presence in the academy itself is constantly questioned. Last year, I was somehow seen as the go-to target. Want to make a grad student’s life difficult? Well, she’s fair game. Usually it’s not okay to state to someone’s face that they pale in comparison to your other students (especially when according to hir (flawed) metrics, I was right at or ahead of hir other advisees). But since it was me, it was completely fine, and the designated point person in the department couldn’t be bothered to set things right.

Furthermore, although there are black women in my department’s faculty, I hadn’t had any scholarly reason to work with them. (They arrived after I finished coursework, and I don’t do African-American/women’s history.) So I had no allies in the faculty who could recognize my treatment for what it was.

All of this is to say that I think there are two things that the book discusses, and only one is the crucial factor in determining treatment in the academy. (Now, I mean, not the 1970s-80s generation of scholars.) I think the issue is less black women’s history–I suspect that white women who have done similar work on black women get some abuse but not to the same degree as these historians reported in Telling Histories. For me, the determining factor is being a black woman in the academy, and while the book was certainly useful and a must read, as one of very few black women not working in American history, I felt like a crucial part of the experience was left out of the book: what happens to those black women who don’t have the intellectual home that these cohorts of women created?

LikeLike

thefrogprincess–I absolutely see your point. And I think Gray and her contributors would agree that the struggles they document here have 80-90% to do with Professing While Black and Female, although I think their struggles to create a new intellectual field of inquiry were fascinating in their own right and important to understand better.

I thought it was interesting that the older contributors to the book (those born in the early to mid-1940s), like the white women scholars of that generation, first wrote traditional (men’s) history books, and only after establishing their credentials thusly were they able to go on and participate in the invention of black women’s history. But unlike you, they mostly wrote African American men’s history books.

I think the book that addresses your experience has yet to be written. I can think of only a handful–as in, the fingers of one hand–of African Americans who write something other than U.S. and African American history. (The ones I’m thinking are Europeanists, medievalists to early modernists, men as well as women.) But I think the fact that that book hasn’t been written is further evidence of the major themes of professional isolation and exclusion that each of the book’s essays addresses.

LikeLike

I think their struggles to create a new intellectual field of inquiry were fascinating in their own right and important to understand better.

Without question, and I learned a lot from that discussion. I’m with you that this should join the Novick/Smith section of “Intro to Graduate Study of History” courses. I also think that b/c it was a series of personal memoirs, I got a better sense of the rigor required to do this work professionally than almost any of the similar books I read in those intro classes.

And as for African Americans not in US/Afam history: yeah, I’m with you, and we’re probably thinking of the same people. I was recently at a conference in my own field; of about 300 people, I was the only African American who wasn’t a part of hotel staff. And without giving too much away about my field, I can say that I was surprised by this development, b/c the field is one in which there are very important and central questions about race.

LikeLike

Just to be clear, you are talking about some area of history, correct? And not social or natural sciences?

LikeLike

We probably are thinking of the same fingers of one hand, thefrogprincess. (Yes, she is a historian, CPP.)

And yet, the mythology still persists among many white historians that black historians are privileged and advantaged by being vastly outnumbered. Clearly, this is a belief that can be held by people who have never been a minority in any environment anywhere.

LikeLike

Pingback: Sunday Reads: Tyrants and Tsunamis « Sky Dancing

Thanks for posting about this anthology. While things have certainly gotten (a bit) better, and we have these women to thank, it’s still really really bad in history for black women, unfortunately. Not to nitpick, Historiann, but this sentence “Because so many of the books by the authors in this collection have won prizes and have come to define the field they invented, those of us who are their peers or who are slightly younger take their success as natural, or foreordained.” is certainly not true for “those of us” who are minorities.

LikeLike

BigBossLady: you’re right, and you’re not nitpicking. I’m sorry! I’m sure my being white is the reason I didn’t think more critically about that point.

But, in partial defense at least for myself, and speaking only for myself: I have (naively) believe that about prominent white women scholars, too. (That is, I’ve thought that their having tenured positions at prestigious unis and prizewinning books and other honors was natural or predestined because they are really good at what they do, rather than an awesome amount of work and a determination to triumph over adversity.) But then I got involved with the Berkshire Conference, and discovered that pretty much all women have some horror story or another–tenure fight, tenure denial, maternity leaves denied or punished, terrible environment, etc. Big name after big name of scholars whose work I had long admired and whose careers I had (until then) envied–they all had their stories to tell.

My need to believe this at one point may also be due to the fact that I’ve also probably internalized some of the career obstacles that I’ve faced, and I simultaneously blamed myself to some extent (or believed I deserved it because I’m not so great), while wanting to believe that some people have charmed lives and careers. I know that doesn’t completely make sense, but there it is.

LikeLike

No worries, Historiann. I agree with you, re: the prominent white women historians. It feels as if both things you identify happen simultaneously, in that big time minority and/or female scholars win all sorts of things, and it feels natural that they do, because they are so amazing, but they also climbed some enormously high mountains to get to that prominence, and we lost too many good people along the way and the mountains seem daunting to us younguns.

LikeLike