I have colleagues who have written articles and books on food history. I don’t consider food history one of my main subfields, but I’ve learned a lot from food historians, and their work has been incredibly useful to me as a historian who works on the intersections of ethnicity, religion, gender, and identity. I’ve learned a lot recently, for example, on the consumption of dog meat by Native peoples in the Americas, and how Wabanaki people might have survived on gathered foods in the Maine woods, winter and summer. (If you find yourself in need of a North woods cure for scurvy, I’m your gal.) The pretext for all of this Survivor Woman: colonial edition research is that I’m writing some book chapters about a little girl right now, and I’m interested in her food ecologies because I think food would probably have been something of urgent and pressing interest to her, especially because I’m coming to the conclusion that she was probably hungry more often than she wasn’t.

I have colleagues who have written articles and books on food history. I don’t consider food history one of my main subfields, but I’ve learned a lot from food historians, and their work has been incredibly useful to me as a historian who works on the intersections of ethnicity, religion, gender, and identity. I’ve learned a lot recently, for example, on the consumption of dog meat by Native peoples in the Americas, and how Wabanaki people might have survived on gathered foods in the Maine woods, winter and summer. (If you find yourself in need of a North woods cure for scurvy, I’m your gal.) The pretext for all of this Survivor Woman: colonial edition research is that I’m writing some book chapters about a little girl right now, and I’m interested in her food ecologies because I think food would probably have been something of urgent and pressing interest to her, especially because I’m coming to the conclusion that she was probably hungry more often than she wasn’t.

All of this seems connected to Anglachel’s “A Taste of Things to Come,” a personal essay about food, social staus, and identity. Here are a few excerpts, but you should just read the whole thing:

I think a lot about food.

I think about what it was like to grow up not being able to afford the kind of food “normal” people ate.I think about cans from charity. I think about having to shop at cut-rate food stores, buy day-old (“used” in my family’s lexicon) bread, have only non-fat dry milk on the shelf, cheap off-brand margarines on sandwiches, big cans of peanut butter we had to stir to keep the oil from separating, and lunch boxes that had books in them because sometimes there wasn’t lunch. I think about a mother too far gone in depression to care what she served her family. I think proudly about eating Hamburger Helper because I could make it myself and have it ready when Dad got home. I think about the way our meals improved as Dad finally got seniority at his job and his pay inched up. I look at the pantry shelf and wonder if I’m hoarding again.

I think a lot about food.

I think about the varying quality of produce between the IGA, the Trader Joe’s the Ralph’s and the Henry’s Market where I live. I remember, living in New York as a grad student, walking around Balducci’s, eyeing the perfect red bell peppers, then sighing and going to D’Agostino’s or the A&P.

. . . . . . . . .I think about the way in which grocery stores and shopping lists become political markers of having “made it.”

. . . . . . . . .

I think about food a lot.

I think about the gendering of our interactions with food – real men eat meat, real women watch their weight, famous chefs, unpaid housework, hunters and gatherers. I think about the way a woman’s mouth is regarded when she puts something into it. I think about stepping on a scale and having my worth reduced to three digits. I think about beefcake and cheesecake. I think about the bones in shoulders and clavicles. I think about preparing dishes you don’t dare consume, fearful of what it will say about you, both the making and the consuming.

I think a lot about food.

I think about the desire to tax “junk food”. I think about the industry of shaming fat people. I think about scarfing down ice cream, ashamed I am doing so because I’m fat. I think about the self-indulgence of watching rock concerts to stop hunger. I think of the anxiety about not ingesting the courant food of the month. I think about the miracle elixers that will save us all from the heartbreak of some obscure condition. I look at case after case of frozen convenience foods and their bar codes. I think about quaint little groceries in the Oakland Hills with prices written by hand onto the shelf tags. I think of relatives who sneer at stores I rely on. I think about the medicalization of food, turning eating as such into a pathology. I think about the transformation of food into a visible sign of personal rectitude.

Fortunately, people in my period (like Anglachel) thought a lot about food, and wrote a lot about food–almost (but not quite!) as much as they wrote about their insecurities that God (or Manitou) had abandoned them, and their confidence that Manitou (or God) would smite their enemies. Captivity narratives, The Jesuit Relations, most travel diaries, and other published primary sources are filled with references to the food people ate–complaining about what other people ate, bragging about what they ate, and in general, using food and the preparation and consumption of food as markers of their identity and status. Food–or abstinence from food, in the form of ritual fasting–brought people together, and the mockery or refusal of an offer to share food was a highly fraught, even political action. Food policed and transgressed the boundaries of savagery and civility, male and female, virtue and sin verguenza, outside and inside the body. (No wonder my post on Hanna Rosin’s article on breastfeeding sparked such heated debate–the breast is perhaps ground zero of the policing and transgression of all of these things with respect to food!)

Food is the material object we have the most intimate contact with on a daily basis. Food is not worn on the body (like clothing) or written on the body (like tattoos or scarification practices)–it’s literally incorporated into our bodies, in the mundane miracle of transubstantiation our bodies perform for us minute by minute. In this sense, it’s probably more important to our identities than our sexual selves, and for modern secular people, our purchase, preparation, and consumption of food is perhaps more related to our sense of personal morality than sexuality.

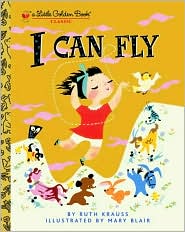

A note on the image above: Go to Found in Mom’s Basement here, and scroll down. Doesn’t the little girl in the Meadow Gold ice cream ads look just like the little girl in I Can Fly, at left? She must be the creation of the same artist, Mary Blair–I love her stylized depictions of midcentury girlhood (below)!

A note on the image above: Go to Found in Mom’s Basement here, and scroll down. Doesn’t the little girl in the Meadow Gold ice cream ads look just like the little girl in I Can Fly, at left? She must be the creation of the same artist, Mary Blair–I love her stylized depictions of midcentury girlhood (below)!

From Found in Mom's Basement

Dammit, now you made me hungry!

Your post also made me wonder, why has food studies become so incredibly popular, incredibly fast, both in the academy and in that public-intellectual-type-sphere with all those tons of popular press books? What’s going on in the culture that this suddenly seems _the_ way to grapple with contemporary society?

Food is the material object we have the most intimate contact with on a daily basis. Food is not worn on the body (like clothing) or written on the body (like tattoos or scarification practices)–it’s literally incorporated into our bodies, in the mundane miracle of transubstantiation our bodies perform for us minute by minute. In this sense, it’s probably more important to our identities than our sexual selves

This is fascinating to contemplate. I look at clothing and fashion in the cultural imagination of an earlier time period, when there is a sort of frenzy and heightened anxiety around that much more than there is around eating. So I wonder, what makes a culture shift its attention from one realm to another like that?

If I ever come up with the answer, I guess I’ll have the plan for my award-winning book! Heh.

PS I read a novel over the summer, Nora Okja-Keller’s _Fox Girl,_ which had all these cool intertwinings of sex and consumption of food. It’s about sex workers/comfort women in Korea serving US soldiers during the war.

LikeLike

Sisyphus–I don’t know why the zeitgeist is the zeitgeist! It is interesting, isn’t it? I too have written about the material and symbolic value of clothing (in Euro-Indian encounters in my period.) In history, I think the interest in food has to do with its intersection with both the historiography of the body (and more broadly, questions of identity and nationalism, for example), as well as with the rise of environmental history’s prominence in my discipline. So, food history (and food studies more broadly) hits a lot of fashionable bases.

I think the history of the body may be where women’s and gender history and environmental history meet, and food is an obvious place for all of these subfields to meet and inform one another. So far, there’s not a lot of work at this intersection (women’s history and environmental history)–environmental history has traditionally been cast as a very guy thing (both in its subjects and its practicioners.)

Thanks for your compliments, and for the reading tip. I read a book by Bich Minh Nguyen called Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, a memoir of her childhood as a Vietnamese immigrant (with a Latina stepmother) growing up in Grand Rapids, MI in the 1970s and 1980s. Her hungers for American food reflect her desire to get away from her immigrant food (and identity) and to be a “real American.” (Grand Rapids is the epicenter of old-line white Michigan middle-class Dutch Reformed conformity…)

LikeLike

One of the things I find most interesting about the “Descriptions of X” that proliferate in the late 17th c is that they go into great detail on food, and try to make food in the Americas match food in Europe.

As for the contemporary stuff, one of my stepsons regularly throws out anything that is past its sell by date. It drives me nuts. I admit, I still just cut off the bit of mold on the cheese instead of dumping hte cheese.

LikeLike

I have been surprised by the number of professional settings where we have been asked to bring a food item that represents our “personal background” (read: racial/ethnic background). Notions of bringing the “food of my people” always makes me leery.

LikeLike

GayProf’s comment reminds me irresistibly of my favorite Margaret Cho bit, in which she describes being on an airplane as the steward goes along offering “Asian Chicken Salad.” When he comes to her row he looks confused, and mumbles, “er.. chicken salad..?”

At that point in the performance, Cho offers an amazing physical transformation, in which she seems to shrink down, her back bends, her face wizens, and she suddenly, and startlingly, evokes a much-older lower-class woman. She peers up, as if at the imagined steward, and says, in this naive voice, “This… this is not the salad of my people!” It was indescribably funny in live performance.

LikeLike

Ha! The “food of my peoples” schtick is something no history department does (at least not one I’ve ever been affiliated with.) If we each brought food from the time period we studied, we’d have one nasty, inedible buffet! Kind of an interesting performance art installation maybe, but not much of a potluck.

What would I bring? Samp, or hasty pudding? I guess I could call it “polenta!” The idea of showing up at a party with a roasted dog holds some appeal to me, if it weren’t for the poor little dead doggie! Since in the East dogs were consumed mostly as a feast that was a prelude to war, that would be a hell of a dish for a back-to-school/first faculty meeting potluck.

Susan: I hear you on the not-throwing-out food bit. I hate to see food go to waste!

LikeLike

Oh, check out the recipes in “Pleyn Delit” — a wonderful medieval-inspired cookbook. I’ve cooked some of these. Not always my taste (the spicing combinations are sometimes weird to modern palates) but very interesting. It’s about time that the rest of us historians acknowledged the centrality of food to human life (ruefully eyes the dinner dishes still to be put away).

LikeLike

In some of the early native communities I’ve looked at– well south of Norumbega (Maine)–Indians learned that the best way to resist, defeat, or control Englishmen was to withdraw, or threaten to withdraw, rather than aggress or attack, leaving them to feed themselves. One of my favorite episodes is from Ralph Lane’s account of an early Roanoke expedition. The English party is accompanying Indians into the interior of the Virginia (Carolina) coast, seeking precious metals, and the Indians abandon them. The men vote to continue inland, even if they have to eat their own guard dogs. Wouldn’t you know, Lane reports, a day or so later they’re reduced to “their dogs porridge, that they had bespoken for themselves” for breakfast. Then they get rescued when Francis Drake makes a deus-ex-machina appearance on the coast to pick them up. I wonder what HE fed them?

LikeLike

I love how the little girl in the ice cream ad and her doll both have the same hairstyle!

LikeLike

“it’s literally incorporated into our bodies”

Therefore food is a major way that cultural ideologies influence the reality of the body. That’s a very powerful feedback loop, and blurs the distinction between biology and culture.

Food studies also intersects closely with animal studies, which is another field that’s suddenly taken off in the last few years. In many cultures a major boundary between animal and human is that it’s alright to eat animals but wrong to eat humans. Different cultures have different hierarchies of which animals can be eaten and which meats are more prestigious, and that can feed into national or racial identities. For example “we’re better than the French because we don’t eat horses” can be a significant part of English/British identities.

LikeLike

I recently read on a website about ‘customs around the world’ that when you come to my home country and visit somebody they will offer you tea. It then explained how it was ok to say no, but some hosts will repeatedly offer it to you and strategies for this. And, while I am quite aware that we have our own customs, it never occurred to me how important this ritual was (and it is a huge part of our visiting rituals). And it then struck me as very amusing how you can engage in food rituals every day and not even think about it until some ethnographer writes it up for you. I think the kind of abdurdity of this resonated as when I went to Easten europe a few years back I was amazed how in EVERY house we visited, I was offered a shot of vodka [or some other similar spirit], which of course is exactly the same behaviour but with a different food at its centre.

LikeLike

Gavin wrote: Therefore food is a major way that cultural ideologies influence the reality of the body. That’s a very powerful feedback loop, and blurs the distinction between biology and culture.

Comrade PhisioProf wrote: I love how the little girl in the ice cream ad and her doll both have the same hairstyle!

Incorporation, reproduction, mimesis: isn’t this what food–and our particular cultural constructions of what’s civilized, appropriate, and nutritious–is supposed to accomplish? I don’t have the right training (anthropology, ethnography, etc.) to interpret it terribly deeply, but that ice cream ad is powerfully suggestive of what we want when we pick up something to eat. We want to re-create ourselves and make the world like us? That’s certainly a HUGE part of what’s at stake in the colonial Americas.

(Also: have you ever noticed, at the grocery store or the library perhaps, how little girls usually have their hair worn in the same style as their mother’s hair? Women with long hair grow long hair on their girls, and women with short hair tend to chop it off. Living dolls!)

LikeLike

Since I went to Cornell, I can assure you that the study of food history is not new — the peer-reviewed journal _Food and Foodways_ used to be edited by faculty at Cornell. The university library rare books department has a large collection on culinary history, as does the Schlesinger Library. The University of California Press has a series on food studies.

Because the study of food and nutrition has roots in home economics, my guess is that other historians didn’t take this work seriously.

As to why this field is suddenly so popular — anxieties about food safety and the impact of agribusiness on the environment no doubt plays a large role. I would also guess that interest in the history of the body has played a role in the development of interest in food history.

LikeLike

I might be wrong about this, but one thing that strikes me regarding cultural perceptions of food consumption (in western culture, at least) is how until recent decades, the consumption of large amounts of high-calorie, high-fat food, and the consequent large waistlines, was considered a sign of wealth and status. In more recent times, it has become quite the opposite – eating high-fat foods and being heavy is often seen as a sign of lower class and social status, while eating leaner foods and being “thin and fit” is associated with higher social class and status. When people would tease me about my waistline, I used to reply that 200 years ago my appearance would suggest to people that I was a lot wealthier than my thinner friends were!

LikeLike

Acquiring food was one of the primary activites of early humans. The switch from hunter-gathering to farming required humans to stay in one place so they began creating permanent dwellings.

As humans learned to produce rather than find food they were able to divert attention to other activities like arts and crafts. As the efficiency of food production increased, larger communities became possible.

IOW – food played a major role in the beginning of civilzation.

LikeLike

Well, where does one begin? I’m deeply in sympathy with Anglachel’s statement. When I asked my late father what it was like to grow up in a large farm family in the Great Depression, he answered with a short sentence that combined sacrific and shame: “We ate macaroni every day and I wore your Aunt Francis’s shoes to school.” Another of my aunts recalled to me, not long ago, that they would awaken to the smell of frying bologna for what would eventually be 10 kids’ school lunches. “Smelled great,” my aunt said, “but fried bologna sandwiches for lunch were pretty soggy.”

I don’t eat much bologna now, but every once in a while my family indulges in fried bologna sandwiches and we recall my father’s penchant for them.

My mother grew up in Nazi Germany and learned under that regime to cook and bake like a professional–but she and my aunt had to trade sandwiches along the railroad tracks during and after the war for coal. My mother’s smoking habit was formed when she was paid in cigarettes to iron GI’s shirts during the Allied occupation–smoking staved off hunger pains.

So my siblings and I were raised with a lot of thought about food and waste. Rarely did we dine out. Sundays and holidays were spent with relatives–nearly every Sunday we went to my great-grandmother’s farm. I didn’t have fast food until high school. In our house we didn’t smell fried bologna when we awoke; we smelled soup. Mom made soup everyday and if you know soup’s history you know that it may be made cheaply and is filling. We suspect that the recipes she handed down would fill a cookbook section called “soup in a time of war.”

I can what’s in my garden and, until recently, was the odd person for putting up preserves, tomatoes, pickles, and peppers. I didn’t make jam this year because I’m out of work and that process is beyond my budget. My friends are disappointed (but only a few of them have returned the jars for re-use)!

Back in 1984 I was amazed at the Super-Sizing of Everything, not only at MacDonald’s but also food sold as holiday gifts. Five-pound canisters of M and M’s, for example. I remember just standing in a department store, thinking about the Ethiopian drought, the rise of homelessness evident in the streets of Reagan’s America, and the sort of (New) Gilded Age excess revealed in the luxury of spending money for candy and other non-essential comestibles. Had economists and historians and other social observers considered food rather than house construction and stocks, they may have been able to predict some of the great disparities in income and health Americans are now seeing.

LikeLike

Heh,”food of my people.” I wonder how many colleagues would eat my childhood standby, stir-fried green beans and spam (with lots of MSG)?

ps To add to the list of Asian American novels about food, _The Book of Salt_ by Monique Truong imagines the life of the Vietnamese cook for Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas; _My Year of Meats_ by Ruth Ozeki follows a documentary filmmaker who interviews families across America about preparing meat dishes. There are many others but those two are my favorites.

LikeLike

And, the standard, PERFECTION SALAD by Laura Shapiro — the book that opened my eyes about the cultural assumptions behind home economics.

LikeLike

The “food of my people” was McDonald’s hamburgers and French fries. My mom was busy. My dad only cooked over open fires. There are many judgements to be made about both.

I keep coming back to this because I’m keep wondering how not eating — as in fasting or in anorexia — fits into this. I also wonder about the use of food as a form of control, both socially and individually.

LikeLike

@ GayProf: What do gay people eat, anyway? I always bring the chips, or the plastic forks and paper plates and napkins, since I have no other model for what an un-womanly female does other than that we don’t cook. So clue me in: What does “our people’s” food look like?

LikeLike

Dr. Righteous: Wait — Eat? And give up my gayish figure?! No way.

LikeLike

Pingback: Making Tacos « Prone to Laughter

Late to the party, I know, but I love this post. I taught several sections of a composition course several years ago built around the politics of food (before *The Omnivore’s Dilemma*), and I always began the class by asking how many people had eaten anything in the last day/week/month that had not been purchased. In none of the sections at fancy urban university did anyone EVER raise their hand, and even here at Poor-State Flagship, a few had just picked some berries from a raspberry bush in the backyard.

The degree to which “consumption” as a concept maps sustenance onto capital is an important realization for all of us to make. My people’s food was a lot of mac-n-cheese, pork-n-beans, and boxed pasta with doctored sauce from a jar. Inexpensive food prepared with care enough to make sure it was tasty and nutritious. As a comparatively affluent adult (or at least one willing to splurge on food over, say, electronics), I take a deep, and very aspirationally classed pride in my love of Humboldt Fog cheese, Muscovy duck breast, and good red wine, a pride that even my critical awareness of the motives hasn’t dampened.

LikeLike