Squadratomagico has an interesting post (and discussion in the comments) about patriarchy: What is it? Where does it come from? And perhaps most urgently, who’s enforcing it? She writes:

Squadratomagico has an interesting post (and discussion in the comments) about patriarchy: What is it? Where does it come from? And perhaps most urgently, who’s enforcing it? She writes:

What is at stake when a rhetorical dichotomy between “patriarchy” and “women” is posited? The way this opposition is used seems to me to suggest the following things:

1. If “patriarchy” and “women” are on opposite sides of a dichotomy, then patriarchy must be an all-male thing.

2. Thus, women are not a part of patriarchy, but fall somewhere outside it. Women may be acted upon by patriarchy in ways that either victimize or benefit them (depending on the women’s status and position vis-a-vis particular men), but they do not themselves perpetuate patriarchy, participate in it, or drive it.

3. If a woman suggests that women sometimes do perpetuate, participate within, or drive patriarchy, then she herself is acting as an agent of patriarchy by blaming women and undermining female solidarity, rather than attacking the real enemy, patriarchy, which is composed of men only. Oh, but wait: huh? Please review the tendentious aspects of this reasoning. I think it boils down to this: women are not part of patriarchy, except when the commenter disagrees with said women. In that case, indignantly accusing your opponent of being an agent of patriarchy, or of “blaming women,” is a convenient means of bludgeoning them into silence while declaiming your own impeccable feminist credentials as a supporter of women. Hence, the tactic poses a false dichotomy between “blaming women” versus “supporting women,” while simultaneously defining debate itself as inherently divisive.

4. Following upon the previous point: feminist politics, for these commenters, appears to be predicated upon strict solidarity for both sexes. The feminist first principle is for women to stick together without dissension or debate, in order to best advance their own collective interests, which are presumed to be self-evident. Feminism thus conceived constitutes a neat counterpoint to patriarchy which, as we already have seen, is presented as an all-male formation existing to best advance men’s collective interests.

I especially like that point in #2: talking about patriarchy this way erases the complexity of patriarchy (and not incidentally, women’s agency too). We don’t think this way about other systems–capitalism, or colonialism, and divide the entire world arbitrarily into either victims or agents thereof. Why do this with patriarchy? In my own work in early American history, it’s quite clear that patriarchy works to the benefit of some men, but that there are many ways in which it disadvantages many men even as they frequently benefited from some aspects of patriarchy. (This was in fact the topic of my dissertation, and a major emphasis in my published work, both in my book and the articles that preceded it.)

For example: enslaved men were able to leverage very few, if any, of the benefits of patriarchy–but there were plenty of free men too who were more often subject to patriarchy than able to lord it over their putative female victims. Not just sons, or servants, or others lower on the “Great Chain of Being,” but householders who are no longer able-bodied fail to live up to patriarchal ideals who were reduced to dependence (and even begging for charity). I have read many affecting petitions filed by disabled English war veterans after King Philip’s War–men who met the highest test of manhood by serving in the military, who were then reduced by their injuries to petitioning the colony to support their families because they can no longer farm their land or otherwise work. If English common law didn’t erase wives as citizens, if the gendered division of labor wasn’t so strict, if Calvinist religion didn’t demand such abject submission from women, and if girls were taught to write and cipher as well as to read, maybe their wives could have better compensated for the loss of their husband’s labor. Those are the stakes in a patriarchal family–all of your eggs (so to speak) are in one person’s basket, and are riding on his health, strength, and goodwill.

Similarly, there were many early American women who simultaneously achieved some advantages from living in a patriarchal society and cooperating with patriarchal institutions even as they too paid a price. Religious women in New France and Mexico performed a delicate dance between the patriarchal authority of the Church they served and its earthly governors, all of whom were men, and the authority they were able (and happy) to wield over their students and in their communities (Indian, French, and Spanish alike) precisely because they too were agents of the Church and conduits of its influence and power. Anglo-American women consented to marriage although coverture erased them economically and legally, because through marriage and by contributing their labors to their husbands’ households, they might become the mothers of children, and even the mistresses of servants and slaves, all of whom were subject to their authority in the household. These same women, as “goodwives” and mistresses, eagerly enlisted in monitoring and punishing the illicit sexual activity of unmarried women in their communities. Because of their own sexual (and usually childbirth) experiences who were authorized to offer testimony in infanticide, rape, and bastardy cases.

Anyone who is interested in the micropolitics of authority and submission in colonial America–or anywhere, really–should take a look at Trevor Burnard’s fine study, Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and his Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World (2004). It’s a chilling account of the relative ease with which a mid-18th century slave master and overseer is able to divide and conquer enslaved men and women alike with a complex combination of rewards and torture, which he bestowed and/or inflicted on enslaved people with whom he was personally and frequently sexually intimate. Thistlewood’s knowledge of their personalities, desires, and their relationships with each other were instrumental to his exploitation of them.

In the comments to Squadratomagico’s post, Susan came up with a brilliant way to think about patriarchy:

What you’ve captured is exactly why there is a patriarchal equilibrium. It’s not about being well-intentioned, or individual relationships, but a system. In discussions of racism they talk about institutionalized racism to get away from talking about individual feelings. Maybe we should start talking about institutionalized sexism — i.e. sexism embedded not in individuals and their behavior but the structures and assumptions of various institutions with which we interact.

Exactly–racism is not a feeling felt by white people that they resent/mistrust/don’t like people with darker skin. Racism is–to borrow from Squadrato’s analysis of patriarchy:

[Racism/patriarchy] is an idealist, rather than a materialist, force within the world — though one that has significant material effects. More specifically, it is a cultural system premised upon a particular set of power relations; [People of all races/sexes] may participate within and reproduce it, for it possesses the formidable power to structure notions of “common sense” and attendant social norms.

I think she takes after me, don't you?

My point in writing about what I called the Breastfeeding Imperative last week was not to criticize women who breastfeed their children, nor to point the finger at them in letting down the entire feminist movement. (I did criticize the “nursing Nazis,” who believe they must enforce the Breastfeeding Imperative on all women, regardless of anyone’s actual circumstances or needs, and whom I have seen and heard in action personally myself, and downthread in the comments I made sport of the fetish many people seem to have for “natural,” although we all worship at the altar of nature very selectively.) Rather, I wanted to examine Hanna Rosin’s proposition that what I dubbed the Breastfeeding Imperative is one of (in Susan’s words) “the . . . assumptions of various institutions [e.g. the family] with which we interact.”

I realize that it may be difficult, or even enraging, for women who sacrificed a lot to breastfeed to read Rosin’s judgment that it probably wasn’t worth it, that it won’t make much (if any) difference in your child’s health, and that it may play a part in undermining feminist goals–but I thought she made a compelling case. My standing as a breastfeeding mother, a bottle-feeding mother, or as a non-mother should have no bearing on people’s responses to this post–I’m a women’s historian who has written about women and men who have had a variety of life experiences vastly different from mine (and thank goodness for that!) My expertise comes from my intellectual training and 20 years as a student and then as a professor of history, not from any personal experiences I choose to claim (or not.) I am Historiann, not Mommiann, not Notmommiann. As Dr. Crazy wrote last night as I was finishing this post,

I don’t think that it’s my responsibility to talk about parenting or motherhood in a way that parents or mothers approve. I’m not hostile to parents or to children or to helping to accommodate colleagues. I’m not judging women who have children, or attacking them. I’m not resentful of them, nor am I envious of them. I don’t look down on people just because they have children, nor do I admire people just because they don’t have children. I don’t, ultimately, judge people by whether or not they’ve procreated. All I’m asking for is the same courtesy. How dare I?

Yeah–how dare you, Crazy? Here’s some more food for thought from the good Dr.: “I think it probably makes sense to consider the ways in which women – whether they have children or not – are inscribed within discourses about motherhood, and the negative consequences of that inscription.” Ya think?

Second image courtesy of The Angry Dome. Thanks, man–I couldn’t have said it any better myself.

OK, people need to stop with all the good posts this week. I have catching up to do!

LikeLike

Brilliant post, of course, but oh how I heart those illustrations! Delicious eye candy, Historiann.

LikeLike

Thanks for the shout-out, Historiann, and thanks for drawing attention to that line about discourses on motherhood. Even as I was writing, I thought that line was probably the most important one, and really it’s the thing that I’m most interested in thinking about. I don’t write directly about my research on the internet, but this is a central piece of my next big project, particularly because throughout the 20th century the tendency was to shut off real inquiry into those discourses and *how they continue to shape women’s lives and experiences* by relegating them to a historical elsewhere. In the first part of the twentieth century, the emblem of this is Virginia Woolf’s suggestion that women need to kill the Angel in the House; in the late 20th century and early 21st century, the emblem becomes the 1950s suburban housewife. The problem with construing discussions of motherhood specifically and domesticity generally in this way is that it sets up a dichotomy of oppression vs. liberation, which as Squadratomagico’s post on patriarchy demonstrates, is a gross oversimplication and actively forestalls critical inquiry.

And these tendencies can be traced not only to authorized “patriarchal” discourses but also to activist “feminist” discourses.

Yes, the personal is political. But if we believe that women are full human beings, and if we believe that women’s expertise is not only traceable to personal (embodied) experience, I think we also have to believe that women have the power to see multiple perspectives that do not reflect their own experiences and that women, especially women who’ve trained for years in specific disciplinary methodologies and intellectual traditions, to analyze and to understand topics that don’t reflect their immediate, personal, embodied experience. That doesn’t seem like that radical of a claim to me, but when it comes to discussions of childbearing, motherhood, and domestic arrangements, and how these intersect with work, there appears to be a disconnect that undermines that claim.

LikeLike

er, have the power to analyze. Woops. Left words out 🙂

LikeLike

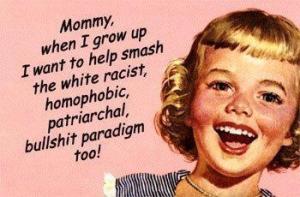

Thanks, guys. Roxie, just go to google images, and type patriarchy, and that little pink postcard with the adorable girl child is one of the first images that pops up! (There were some other good ones, but that one seemed especially appropriate.)

LikeLike

I completely agree that women like men are often complicit in patriarchy, and that it’s an important question to try and figure out where those lines are. I’m trying to figure all that out myself. I also really liked Susan’s proposal: “Maybe we should start talking about institutionalized sexism — i.e. sexism embedded not in individuals and their behavior but the structures and assumptions of various institutions with which we interact.” I think that’s a great idea – I also think maybe we should start talking about feminist responses to that institutionalized sexism. An action plan, as it were.

Motherhood is one of the most powerful discourses (for mothers and for the, what did Crazy call them? the unencumbered). I never meant to suggest that one has to be a mother in order to have a conversation about motherhood, or that the opinions of nonmothers are somehow less legitimate. I identified myself as a mother and a feminist in the earlier post *not* as an attempt to silence others who a) weren’t mothers and b) didn’t agree with me, only as a way of saying – the experience of being a mother and a feminist has shaped my lived experiences of these problems and therefore my view of them, in the same way that my middle-class midwestern roots have.

(A side note: I held back from more of the Rosin conversation largely because I was unhappy with myself and the way I had framed my comments on the topic. I think that I viewed Rosin as doing exactly Squadro detailed above (blaming women in order to shore up her feminist credentials) and yet my post on Rosin did the same unintentionally (because I am a bit emotional, and because I was in a hurry and didn’t think it through carefully enough.) My main issue with Rosin wasn’t that she interrogated the notion of breastfeeding benefits or the social-political-economic negatives for women of doing so – I definitely see those negatives. The problem for me is perceiving those negatives to be there because of the BI; my opinion is that negatives are there because of *structural and institutionalized sexism* rather the mode by which a person gets milk into a child. My contention is that even if every mother bottle fed, they would still face the same negatives. I don’t think we can, historically speaking, make the argument that bottlefeeding “liberated” American women when it began to be more widespread in the 40s and 50s. [At the same time, I see how BI + no political change for the advancement of working mothers = patriarchy equilibrium. But again, that’s the situation in my opinion of all working mothers. We don’t support working mothers because culturally and socially we secretly think they should be at home with their children, and the patriarchal structure tries to force them back into the home. That’s where I see the institutionalized sexism.] Now the discourse of what makes a “good” mother or a “good” woman is a different problem, and definitely a powerful one, one that affects all of us all the time, as Crazy said, and definitely one we all need to interrogate all the time.)

LikeLike

Glad my thoughts were useful — and thanks for the reference to Burnard, which is terrific, and a great book to teach, because it lets you do gender and race in really complicated ways.

Some years ago, I taught a seminar on “Race, Class, and Gender”. As we went in, my co-instructor and I made it clear that we were interested in systems, not individual feelings. (Needless to say, we met huge student resistance.) And I think this is a vital move. What intrigues me — in connection to Perpetua’s comment — is that somehow feminists have allowed the response to these systems to become personal rather than social. And part of that is that we experience them as personal issues — as mothers, as unencumbered people, spouses,workers, caregivers, etc. But we’ve lost the feminist institutions that helped 1960s and 1970s feminists act as if these were indeed systemic rather than personal. (An interesting historical questions about how we’ve lost that. . .) So we marry a feminist man who will follow us to a job. Great. But that doesn’t solve the problem of patriarchy. Nor does whatever personal solution we may make to the challenges of being a mother, partner, caregiver, or human in an academic workplace.

Joan Kelly wrote that “patriarchy is at home at home”. Women, especially heterosexual women, literally can never get away from it. And that’s what makes these conversations so hard.

LikeLike

Susan, I can’t emphasize enough how valuable I’m finding your contributions to this discussion. It’s really making me challenge my own thinking, and the (unconscious) behaviors/ attitudes etc I’ve been expressing. It’s so hard to disentangle the personal from the systemic, especially when the personal is also painful series of gut-wrenching choices.

How can we work to replace those lost institutions?

LikeLike

Perpetua, thanks for coming back to engage this subject again. I think you make some really great points in your comments, but especially this one:

“We don’t support working mothers because culturally and socially we secretly think they should be at home with their children, and the patriarchal structure tries to force them back into the home. That’s where I see the institutionalized sexism.”

Right on. Rosin’s point, as far as I can tell, is that the BI enlists women in this too (how can it not, since it’s they who have the milky breasts?), and that the inflated claims about the value and importance of breastfeeding are wielded by some women as bludgeons against others, perhaps because they need/want the status and validation of conforming to the BI. (This may be especially valuable to women who may have left behind a career, either temporarily or permanently, in order to nurse a child.)

I also think you’re entirely right that “even if every mother bottle fed, they would still face the same negatives. I don’t think we can, historically speaking, make the argument that bottlefeeding “liberated” American women when it began to be more widespread in the 40s and 50s.” Middle-class American women weren’t liberated from domesticity then–but it was defined differently, as illustrated by the shift in our language from “housewife,” with an emphasis on domestic labor and service to a husband, to “stay-at-home Mom,” with an emphasis on motherhood and service to children. Women in the 1950s and 1960s weren’t expected to be on call for their children the way they are now. Children occupied a much smaller slice of women’s time 50 years ago than they’re supposed to now for people who are out of the paid labor force.

Dr. Crazy–thanks again for your post. The discussion over at your place has been good–although now I see some parents engaging in language-policing this morning. It kind of reminds me of a comment I overheard about the New York Times’s obituaries for every single person who was killed in the World Trade Center on 9/11/2001: so absolutely no one killed in the terrorist attacks was a jerk? All of these people were saints? I don’t get why it bothers some parents to hear that other parents are shirkers or jerks at work. If you’re not a shirker or a jerk, then it’s NOT ABOUT YOU.

LikeLike

Okay, I’m going to be gauche and part quote/part paraphrase (with a bit of added emphasis) from the conclusion of my forthcoming book (on medieval women and law), because I think what you say in this post is exactly what I’m getting at:

“[Explanations of discrepancies between “the system” and women’s observable behavior in terms of subversion alone] are problematic because they rest upon an assumption that female agency with regard to the law can only be couched in terms of resistance, implicitly presenting women as the victims of historical processes in which they, unlike men, had no say. I would argue that relationship between women and law – even a law that seems to herald a change for the worse for women – should not always be read as oppositional. Through the process of litigation, medieval women participated in shaping the legal culture that in many ways influenced their lives.”

This is one of the most important things I’m trying to get across, I think.

LikeLike

Notorious: what a great idea for a book! Historical actors don’t know and can’t see what’s coming 50 or 100 years down the road–collaboration with a bad system in order to alleviate one’s immediate personal miseries seems like a bargain most people would take, even if it meant collaborating in a system that will eventually undermine people like them further down the road.

(This is why revolution is so difficult to achieve.)

LikeLike

Historiann, I completely agree that BF can be (and is by some) used to bludgeon women, but I have to say the extent and breadth of the scientific information on the topic is relatively compelling, no matter what Rosin argues; the BI initiative is essentially a global public health campaign to help women and children. That doesn’t mean of course it can be (and isn’t) co-opted by the patriarchy – I think my larger point is that all of the experiences of being women and mothers can be co-opted this way (through the discourse of the “good woman”) but that it isn’t motherhood per se that’s the problem (in the parallel, that BF in and of itself isn’t a problem) – perhaps just the way it is being instrumentalized in the United States at this moment?).

I also completely agree about domesticity in the 40s and 50s. I don’t know if you ever watch Mad Men, but the “mothering” of Betty (the homemaker) is often vilified by the blogosphere because she doesn’t conform to their modern ideas of the obsessed-with-children “helicopter” parenting style that has been adopted in recent decades. But the helicopter style of intense and competitive parenting is also class-specific (though it may be spreading) and doesn’t reflect the realty of every American woman. And while I see that the rise of such parenting styles is clearly connected to the demonization of working women in the 80s (including the demonization of day care), it also seems to me connected to a separate phenomenon of the growth of narcissistic capitalism & viewing children as commodities/ status symbols (it’s all about the right pre-school and the right stroller and the right mind-enriching activities – I thought Brigid Jones’s Diary actually had some pretty hilarious commentary on this phenomenon).

Ok, I promise now I’ll just follow the conversation for a while!

LikeLike

I’ve been enjoying the conversation here and also on Dr. Crazy’s blog. Another unspoken, structural element of the way motherhood is discussed is that it is a “private” endeavor–as part of the nuclear family in a single-family home. One of the most powerful insights of feminism (1st as well as 2nd wave) is that parenting should ideally be a more cooperative endeavor. Nobody talks much about communal kitchens, public playgrounds and the like anymore. This isn’t an argument for parents to “shirk” work duties; but rather an attempt to think about the structural constraints on work/family life.

LikeLike

Widgeon: great points. As many have pointed out, “shirking” might just be the least odious of several impossible choices. Parents (esp. mothers) are truly on their own, because of our cultural ideal of the disaggregated nuclear family.

Working on common solutions seems like a great place to start: it seems like academic departments could easily enlist a work-study student to run a nursery in an unused classroom or lounge, so that the children’s parents could attend faculty meetings. (This would be very affordable if all of the participating parents chipped in $5 or $10.) I don’t think too many child-free people would object to this, since it would facilitate a more equal distribution of service work.

Friends of mine in Fort Collins live in “co-housing,” which is kind of like a suburban co-op condo complex with certain extra privileges and responsibilities. Everyone shares a common green, instead of mowing and feeding their own private patch of grass, and the community maintains it and buys nice playground equipment for the children. There is a shared community house with a communal kitchen, where the community meets weekly to discuss issues/governance, and they take turns cooking dinner there.

LikeLike

“it seems like academic departments could easily enlist a work-study student to run a nursery in an unused classroom or lounge, so that the children’s parents could attend faculty meetings. (This would be very affordable if all of the participating parents chipped in $5 or $10.)”

You’d think, right? But running any kind of multi-family paid childcare (beyond certain very informal arrangements in private homes) technically requires a license, and a license requires inspections and background checks and all that. The licensing is different for kids under 2 and over 2, among other complications. Does the room have an attached restroom? Uh-oh, now you need at least three undergrads, at least one male and one female, so there’s someone to accompany kids to the restroom down the hall (and still two back in the room).

So it’s not actually legal to round up a couple (or three) undergrads and pay them to stay in an unused classroom entertaining a bunch of kids they don’t know, kids who may or may not bring their own toys, blankets, diapers, or snacks to endure the length of a faculty meeting. And if a kid is injured in a campus room not licensed for childcare…

Or at least, a version of this is what I’m always told when I ask about finding a student to help with my kids during on-campus events, or when I ask whether childcare is offered during a conference. It seems like a good idea, but it’s definitely not a simple solution.

LikeLike

Thanks for the link! The ideas explored there had been brewing at the back of my mind for quite some time; certain interventions in the discussion of your previous thread on breastfeeding finally inspired me to articulate them more clearly.

LikeLike

As someone who buys the idea of patriarchical equilibrium (thanks to your previous posts), but who was confused by the post/subsequent discussion of breastfeeding, I found this latest post VERY helpful. As others have already stated, I think it is essential to foreground the *system* (structural sexism) and the ways it intersects with other systems such as class, race, and capitalism. By understanding how a system works can we better figure out how to resist it.

On a personal note (as a stay-at-home father), this post helps me make sense of the ostracism I regularly experience (from perfectly nice people), the (needless) guilt my wife feels for not meeting the societal expectations placed on her as a mother, etc. etc. So, thanks for that as well.

LikeLike

So it’s not actually legal to round up a couple (or three) undergrads and pay them to stay in an unused classroom entertaining a bunch of kids they don’t know… It seems like a good idea, but it’s definitely not a simple solution.

Another “invisible,” gender-neutral-on-its-face, way the institutions of patriarchy function. It’s the same for dads, isn’t it?–and there are undoubtedly real, identifiable dads whose academic work has been impeded by this problem. But the impact falls unevenly–which (in a slight shift) is why conservative jurisprudence has sought to reject disparate impact as prima facie evidence of invidious discrimination, insisting instead on specific evidence of intent in the case at hand.

Late 60’s feminism coined “the personal is political” because women, in CR groups and elsewhere, found that the level of personal experience opened onto the level of institutions. If that connection was weakened or broken in the 70’s, part of the reason is surely that the challenge to institutions, after winning some genuine victories, was forced into retreat–the death of ERA makes a good, though arbitrary, marker; as with the labor movement, anti-racism, and LGBT rights, the turn toward pushing the institutions backward (rather than defending some the territory won in those early years) has been heralded (Obama! Sonia Sotomayor! et al.) but in this old-timer’s judgment it hasn’t yet arrived. “narcissistic capitalism” (Widgeon) and “our cultural ideal of the disaggregated nuclear family” (Historiann) not only turn the attention back to the domestic sphere but sever the connection between that sphere and the institutions it ; re-taking the offensive will need, I think, to include rediscovering and reaffirming that those connections are real. My friend Radfem Family Lawyer (Oakland CA) tells her clients, when they express shock at the inequity of the law, “This is what patriarchy looks like when it’s happening to you.“

LikeLike

Tom: always happy to help. Your wife should stop feeling guilty NOW! And you should too. Just stop it NOW!

Penny: I suppose you’re right. But, I have colleagues who pay students to babysit for them at home and sometimes in their offices while they’re in meetings–so I just thought it wouldn’t be a bad idea to try to pool resources. (Besides, kids almost always prefer to play with other kids, and not grownups or other babysitters.) But for all of the reasons you suggest, it has to be on the down-low and without any kind of institutional imprimatur.

LikeLike

Sigh. “some of the territory, and “the institutions it serves.” Damn spellcheck.

LikeLike

collaboration with a bad system in order to alleviate one’s immediate personal miseries seems like a bargain most people would take, even if it meant collaborating in a system that will eventually undermine people like them further down the road.

I think that’s a huge thing people need to realize about this kind of issue; and it doesn’t even have to be one’s own miseries. Sometimes, there will be a real conflict between helping out an individual (e.g., supporting a wife who’s discouraged by the current system from providing for herself) and working for change (trying to allow women to provide for themselves).

Without recognizing that, you can end up thinking that, once you’ve identified something as an unfair social arrangement, you can end it by a simple act of will; and that turns into both stupid essentialist anti-feminism (“we’ve all* agreed that women should be equal, so if more women than men are doing housework, it must be because they naturally love it!”) and simplistic, uncompassionate “feminism” (“women who don’t find fulfilling careers are just brainwashed fools who don’t understand what they could be doing!”).

(similarly with racism, etc., of course)

*”all” here used in the sense of “not actually all”

LikeLike

Sulpicius–welcome, and great point about the “bootstrap” theory of social change. (Or, if you prefer, the Nike “Just Do It” theory of social change.) This connects back to some conversations we’ve had here about Whig history, women’s history, and feminist history, and how the belief in progress is incredibly blinding and even undermining of real change.

You’re exactly right about the consequences of this “Just Do It” ideology–if you don’t “just do it,” then it meanst that the system you’re trying to resist is natural, or good, or so overwhelmingly powerful that an individual’s efforts don’t really matter. (Thanks again to Susan for reminding us to think about systems rather than individuals here!)

Rootlesscosmo–good to hear from you, and thanks for bringing up Consciousness Raising. I think the women (and men!) of my generation need a really big dose of it. Maybe that’s the kind of institution Susan was talking about when she noted that 60s and 70s feminism was more focused on the system than on individual/personal liberation?

LikeLike

My impression is that there are many bloggers out there who are already talking about sexism/misogyny in this way. Ones that immediately come to mind are Zuska, Female Science Professor, Young Female Scientist, Amanda Marcotte, Isis the Scientist, Janet Stemwedel, Absinthe (although I think Absinthe has shut down her blog), me, DrugMonkey, and Abel Pharmboy. I am sure I’m forgetting others, and obviously, this is skewed towards science bloggers.

LikeLike

I like Widgeon’s point about mothers’ parental responsibilities being classified as a private endeavor. This alienates many things that primary care-givers (mostly mothers) need to do from the routine of the workplace and turns what are perfectly normal issues in the course of parenting into special requests. They are only special when the workplace is defined for a no-parental-obligations worker.

As far as I can tell, women are open for criticism no matter what we choose to do wrt feeding our babies. The institutions and communities in which we exist, not so much. What was feminist in the decision I made was that I made it and then proceeded as though I expected to be respected (irrespective of the decision).

And now, an anecdote about breast feeding. A friend was derided by all sorts of people, family and strangers alike, for breast feeding her children back in the 70’s. She was told it was indecent and would lead to sexual perversion in her son. Yikes.

LikeLike

truffula–eeeewww! “Indecent?” Well, that still happens–women get escorted out of Wal-Mart all of the time for breastfeeding there, which is outrageous.

Yes, whatever women do, they’ll get an earful. The point is not which choice women make–the point is that it’s seen as a provocation whenever a woman makes a decision. She has to be discipined, scolded, and lectured that she’s made the exact wrong decision, and all kinds of people feel authorized to let her know.

LikeLike

truffula – “What was feminist in the decision I made was that I made it and then proceeded as though I expected to be respected (irrespective of the decision).” that’s exactly how I felt and feel about my (mothering) decisions. . . A mommyblogger posted a while back that a big billboard in Canada that displayed a small girl pretending to breastfeed her doll had to be taken down because people thought it was “obscene.” ‘Cause breasts are just for men, I guess.

LikeLike

I would second Historiann’s recommendation of Trevor Burnard’s outstanding book, but with a caveat that I think is relevant here. Burnard does an excellent job of showing how Thistlewood the overseer manipulates patriarchal privilege within a slave system as a means of enhancing his authority. But the book is very much a “top down” affair, written to recover the mindset of an eighteenth-century slave owner. (To be clear, the author offers no justification of Thistlewood’s actions, merely explanation.)

I have found this issue more perplexing when analyzing power relations from another perspective, that of slaves challenging the slave system. As Historiann notes, enslaved men could rarely exercise patriarchal authority in the ways white women did. But in my research I have found that this was one of the primary pressure points in which they challenged the slave system. To use a concrete example from my own work, I have uncovered a fascinating incident in which a slave owner–who fancied himself quite a Doctor–quarreled with an enslaved man–himself a healer–over the right to treat the enslaved man’s wife when she was sick. These men fought a power struggle over access to a woman’s body.

Examples like this–and I think one can find many similar examples in the archives–make me wonder about questions of system, agency, and resistance (a point Notorious and Historiann bring up in their comments above). Given how intertwined race and gender were in the slave plantation system, what can we make of actions that seem to subvert racial power while (perhaps) reinforcing patriarchal power? For an enslaved woman to appeal to her husband to protect her from a master’s ministrations–does this action reinforce patriarchy? I should note that in the example I cited from my own notes we do not know how this sick enslaved woman felt about the situation.

(I apologize for throwing my own interpretive problems on the collective lap of this blog’s readers. But the debates over the last few threads have made me question what I thought I knew about race, slavery, and masculinity. In a good way. I hope.)

LikeLike

But we’ve lost the feminist institutions that helped 1960s and 1970s feminists act as if these were indeed systemic rather than personal.

What now? What institutions were these? How did they let feminists act as if sexism was systemic and not personal? How did that work? I don’t know what you’re referring to and everyone else seems to… I’d really like to know!

LikeLike

I know Historiann has flogged this more than once- but if you want to understand patriarchy as a system, you can’t do better than Judith Bennett, History Matters.

In thinking about resistance to power systems, I find that Foucault is quite useful, as he suggests (and if we are flogging books this is what I demonstrate in my forthcoming book 😉 ) that through resisting to a power system we reinforce the system. By participating in it, we continue to give it life- because power systems are not static but adaptive to the resistance they encounter. I also think this is why patriarchy is an unpopular concept- because to change it demands more than resistance, it demands a paradigm shift. And that is one scary concept, but (rather ironically) also very difficult to envision.

LikeLike

John S., I love your story — I wish there were always ways to get at the enslaved experience of slavery. . .

Human, I was thinking about things like CR groups. Which were institutions, albeit informal ones.

LikeLike

Huh. Why did people stop having them, if they helped so much?

LikeLike

I think the whole idea of post-feminism has encouraged the dismantling of such institutions. Some groups started pushing the idea that we no longer “need” feminism because women are equal now. In that social-political climate, it’s difficult to radicalize people, or convince them that such institutions are necessary or relevant. At the same time, the dismantling of those institutions served to isolate women (as Susan pointed out) – the more isolated we become, the harder it is to come together. (Any body who spends a lot of time on mommyblogs can see how lonely, frustrated, emotionally overloaded, and unhappy many mothers are, working and at home. The number one thing they say is that they are lonely, they have no support system. Keeping women alone keeps them from attempting a paradigm shift. All they can then handle is their own lives and nothing more. And I don’t keep meaning to bring up working mothers as though that’s the most important issue facing women, it just happens to be the one I’m immersed in at the moment.)

LikeLike

Not trying to hijack the thread, and in general your analysis is enlightening to this non-historian. I have a question though (as an admirer of the great Marilynne Robinson): is it really true that “Calvinist religion” demanded “abject submission from women” more than other religions? More than Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, Judaism, and so forth?

LikeLike

So many great conversations here and at Dr. Crazy’s. I’m really enjoying them! I frequently teach courses on gender issues, most recently a course on Gender and Technology. Talk about systems! I blogged many of my thoughts at my own place, some of which have been expressed by your commenters as well.

I just wanted to say here that nothing has complicated my perception of myself as a woman or as a mother than being at home full time. I’ve done this twice in my life and there’s something unsettling about it. It’s like being when Neo found out about the Matrix. Sure, I’ve read books about motherhood and the ways in which society denigrates or elevates mothers, but the reality doesn’t sink in until faced with daily reminders. Much of it is subtle: the expectation that a parent is available at 3 to retrieve children, the look from a colleague when you explain that you’ll need the day off because school is out even though it’s not a holiday, the feeling you get when you get your Social Security statement and there’s a big fat zero for certain years. Some of it is blatant. Being accosted for breastfeeding or not. Being asked about why you couldn’t make it to the school play. Being told that it’s a really good thing that you don’t work cause that’s good for the kids. There are too many other roles where people feel free to tell you what they’re thinking about your personal choices. Choices, I might add, that don’t always feel like choices.

I feel guilty for being at home. When I worked, I felt guilty for being at work. When I think about working, I feel guilty. Where does all that guilt come from? Those expectations Tom mentions above. Feminists expect me to work–to have it all (I am a child of the 70s and then the 80s feminist movement). Traditionalists expect me to be at home. So many conflicted emotions. Someone upthread said that women at home can’t escape the system ever. That is so right. I feel it every day.

LikeLike

Laura: why don’t you just do what’s right for your family and ignore everyone else? Say no to the guilt!

snowblack: I didn’t mean to imply that Calvinism demanded more “abject submission” than any other religion–just that that is the kind of religion that was dominant in 17th C New England, where my particular example came from.

LikeLike

I’m late to this whole conversation as I’ve been away, but have really been enjoying (and learning a lot from) the conversations here and at at Dr Crazy’s and Squadratomagico’s blogs.

I wanted to pick up one comment raised a few times above, which is the allusion to the loss of unified feminist institutions (CR groups etc.) of the 1960s/1970s, and the implication that this may be limiting our ability to challenge structural sexism in a ‘post-feminist’ age. I guess the problem I have with this relates somewhat to Dr Crazy’s comments re: the authority of (parental) experience, in that it seems to assume we ‘all’ (as women and feminists) once had some unified subject position grounded in a common experience from which we could launch our critical analysis of and challenges to patriarchy.

I see (in Judith Bennett’s book and elsewhere) a sort of nostalgia for a time when all feminists supposedly recognised a shared experience that informed our politics, but I don’t think this is actually the case, nor do I think a sort of pining for this ‘lost’ past (if it ever really existed) is particularly productive. Like patriarchy, feminism is not a single monolithic entity or movement, but comprises many and dispersed relationships of power. Those relationships of power need themselves to be interrogated so we can understand how they work, and how they may be contributing to the perpetuation of some aspects of patriarchy that privilege (some) women, as well as men. There are, I think, elements of this in the way women often police other women over their career/child-bearing/partnering choices.

I write this from a position of having recently studied the on-going conflicts between secular French feminists whose feminism is grounded in a liberal, republican tradition and French Muslim feminists who argue from quite a different historical perspective. (The debate was sparked by the ban on Muslim girls wearing headscarves in French public schools.) I’m not really sure where I’m going with this (it’s late and I’m a bit rambly), but I think it’s important not to use terms like ‘patriarchy’ and ‘feminism’ as though they refer to self-evident homogeneous categories, and as Squadratomagico has pointed out, to resist the pressure to see them as a ‘natural’ dichotomy.

LikeLike

Bavardess–great points. This nostalgia for a more unified past is something that I picked up on too in Bennett’s book, although she denies it!

Feminism is indeed an umbrella term for a very diverse set of ideas. It’s good (and even essential) to recognize this–but it does lead to internescene conflicts.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed Bennett’s book, but I also got quite a different perspective by reading Joan Scott’s review of it (which was pretty harsh, but she makes some excellent points about essentialism, and questions of ‘who’s feminism?’). If you’re interested, the cite is –

Scott, Joan W. “Back to the Future.” History & Theory 47, no. 2 (2008): 279-284.

I think now that feminist ideas (in their various forms) have spread beyond the western world and morphed into many diverse responses to particular local conditions, we are really going to have to let go of the idea that there can be any single feminist political movement with a common set of ideals. The challenge, I guess, is to effectively empower women to challenge and change unjust and unequal conditions wherever they are in the world without having that unified political platform to drive activism (and without imposing any preconceived ideas, based on liberal, western, broadly Judeo-Christian values, about what constitutes ‘unequal’ and ‘unjust’).

LikeLike

oops – typo. That should, of course, be ‘whose feminism?’.

LikeLike