Inspired by this post at Feminist Law Professors, headlined “French Court Rules Virginity is Not an “Essential Quality in a Bride,” I’ve been thinking a lot about virgins today, and the concept of virginity. (The linked story is about a French Muslim man who sought and obtained an annulment from his bride because she wasn’t a virgin. An appeals court ruled that “a lie that does not concern an essential quality is not a valid basis for annulling a marriage.”) I don’t think “virginity” is a reasonable or meaningful category for describing people’s lives today for a number of reasons, mostly feminist and pro-gay ones, but I have questions about the history and etymology of the word virgin and the state of being a virgin, which is to say, “virginity.”

A little background here: I have a young friend in a Catholic Kindergarten who is learning the “Hail Mary” (“blessed art thou among virgins women”–sorry about the error) and singing songs like Silent Night (“round yon virgin, mother and child…”), so a word previously not in hir lexicon is coming up on a regular–nay, daily–basis. So I’m expecting (and dreading) the question, “what’s a virgin?” My canned answer is “an unmarried woman,” and I’ll hope that flies. This eventuality has led me to ponder the roots of the word “virgin” and of the concept of “virginity.” Was “unmarried woman” the original meaning of “virgin,” or was the original meaning connected to a specific kind of (lack of) sexual experience? When did the marital and sexual connotations first collide in this word? Was it ever a term applied equally to men and women?

Happily, a number of medieval studies types read and comment here, so I’m calling on you all specifically: Tom at Romantoes, New Kid on the Hallway, Notorious Ph.D., Squadratomagico, and Another Damned Medievalist at Blogenspiel, can you help? (Anyone else I’ve missed, please chime in–I’m just listing the people you can track back to a blog somewhere.) Am I totally off-base in thinking this has something to do with Latin, Norman French, or Anglo-Saxon? Are there any interesting titles you’d recommend that discuss the history and etymology of this word?

One other observation: Catholic education introduces a lot more violent, sexual, and otherwise very adult themes into a child’s life than a happily sanitized modern secular education. This is not a complaint–I frankly think that children are patronized too often, and then they’re subject to commercial exploitation by sexualized and violent images and products without having the tools they need to process and deal with them appropriately. Are any of you familiar with St. Michael’s Prayer? It’s really a trip to hear a 5-year old recite it before tucking into a meal!

There are indeed male examples of the value of virginity in very early Christianity (see Peter Brown’s “The Body and Society”). But don’t blame the Christians for the link of female virginity (specifically physical) and eligibility for marriage: that’s the Romans you want to be looking to, there. Probably older groups than that, too.

Interesting point: lack of (physical) virginity is not a legal impediment to marriage in the Middle Ages (this is especially important for widows, but also for first-timers). It does, however, make a woman a less desirable prospect, thus necessitating other things to balance that out.

But a value on male “virginity” in the Middle Ages? In an age where prostitution was legal? No, I can’t really think of anything, except in the context of clergy and saints.

LikeLike

…and I now realize that I’ve answered a question that you did not ask. And I’ve been looking through my books for where and when the conceptual link happens, and I’m coming up with nothing. You might try James Brundage’s “Law, Sex, and Christian Society.”

LikeLike

Could you do me a big favor and:

1. Go to law school.

2. Become a legal academic.

3. Blog at Feminist Law Professors

Because your posts are awesome!

LikeLike

The French adjective for a single person is célibataire which, to my mind, would suggest that at one time, lack-of-sexual-activity and the unmarried state were synonymous.

LikeLike

You’ve clearly never had the delights of experiencing an Orthodox Jewish day school education. Think: Old Testament, scary, angry god all the time. My friend’s children once came home afraid that their city would be destroyed like Soddom and Gommorah.

LikeLike

The actual text of the Hail Mary:

“Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee; blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen. “

LikeLike

Thanks, Servetus–not being the beneficiary of a Catholic education myself, I must have misheard or misremembered this.

There still are a lot more virgins in the mix these days. Notorious, thanks for your thoughts–all of which are relevant! And Meg, you’re right that “celibataire” is a telling clue. (Your story about the Jewish day school is pretty much in line with my thoughts on sectarian versus secular schools. They give children something to be frightened of, if they’re fortunate not to be frightened by everyday life–as in family problems/instability, hunger, poverty, etc.)

LikeLike

And, thanks, Ann! (You could just have a blog called “Feminist Profs” and save me the trouble of going to law school. I’m just sayin’.)

LikeLike

The English virgin is derived from the Latin “virgo,” plural form “virgines.” My dictionary suggests that the primary Classical meaning of the Latin word is specifically a woman who has never had sex. A secondary, transferred meaning is a young or unmarried woman. Beginning with the Church Fathers, the word sometimes is applied to males: examples from Tertullian and Paulinus of Nola are the two references provided.

Medieval secular culture placed a high value on female virginity when writing about young women, both as an indicator of good morals and, of course, as a desirable quality in a bride entering her first marriage. (For re-marrying widows, of course, there would be a high value placed upon her chastity since becoming a widow). The medieval Church placed a very high value on virginity for both sexes. I think it’s indisputable that this quality is more emphasized in religious writings about women, but it is not infrequently found as an encomium for men as well.

LikeLike

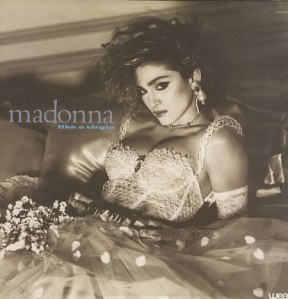

Wow, and I thought this was going to be a post about Madonna and A-Rod! I knew that year of Latin back in 9th Grade that the commonwealth made me take and that Mr. Steer gave me an F in (as in f’in…) wasn’t going to do me any good. All I can think of is that early Americanist commonplace that the Latin word for “man” shares the root “vir” with words like “virtue” and “virile.” But beyond this, I knoweth not…

LikeLike

About that “Hail Mary” error: inexcusable! In my defense, virgins are on the brain because the child dressed up as Saint Cecelia for the All Saints’ Day Mass a few weeks ago. Ze was a Roman (third century?) Saint whose main claim to fame was her commitment to virginity. (Her father wanted to marry her off to a Pagan, but she refused and even converted the Pagan before her father cut off both of their heads.) Now, that’s an impressive story for a 5-year old to have to assimilate. Which part is more disturbing: the forced marriage, or the head-cut-off by your own father part?

The little boys who dressed up like St. Patrick or St. Francis had it so much easier.

LikeLike

I’m not a Christian. It’s just a matter of citation checking.

LikeLike

Ah, but what about those poor boys who dressed up like St. Stephen, who was stoned to death? That is the question 🙂

Slightly off topic, but the decision that virginity is not an “essential” quality made me think of the fact that while virginity was not an “essential” (or likely) quality for prostitutes in olden times (don’t you love my historical specificity here? I’m thinking of 16th to 18th century, I suppose, but I’m a lit person so you’ll have to excuse my muddiness with dates), it *was* however a desirable quality (and one that often appeared in pornographic novels) – one that would get a prostitute a better price. Thus, the practice of orchestrating counterfeit maidenheads, using things like pigeon’s blood (eew) to simulate the blood that comes with the breaking of the hymen.

In other words, virginity being deemed “inessential” in a wife doesn’t necessarily comfort me 🙂

LikeLike

What squadrato said. I found the additional (very exciting) information that it comes from “a young shoot, a twig,” which may or may not be correct. Related to various words for “rod,” FWIW. Comes into English via Old French. Anyway, yes, there is praise for virginal men (who are still frequently described as “warriors of Christ” and have to actively resist temptation by all sorts of ebil nubile women, sent, of course, by the Devil). But I do think the term is pretty clearly originally about women who haven’t had sex, and it gets transferred to everything else.

While virginity was *highly* valued, I also have the sense (possibly from anecdotes) that once you have actual marriage and birth records in the 16th c., a LOT of those babies show up before 9 months after the marriage. So the ideal of virginity may be quite distinct from the reality, at least when you’re looking at non-elite women. (For elite women I would say this was NOT the case, since you have so much riding on legitimate inheritance.)

LikeLike

I like Squadrato’s contribution, though I wonder if the dictionary editors were perhaps making their own assuptions (regarding the “woman”) part. I also found myself wondering about the “vir-” part of “virgo” (vir = man), though that’s most likely a spurious connection on my part.

I think now that the original question may need rethinking. Which came first: the girl, or the sex? Which was later tacked on? My own massive Latin dictionary suggests that the sexual meaning came first, and the later, more metaphorical meaning of a young or unmarried woman was added later (the first uses seem to be in Ovid, Virgil, and Horace). The sexual “virgin” could be applied equally to men and women, but in practice, it seems to have been applied to women much more often — possibly because legal and social norms in Roman society (and others!) emphasized premarital purity for women in a way they did not for men. Until, of course, early Christianity, when sex was considered a distraction for those whose eyes were on heaven, expecting the return of Jesus any day.

That’s the best I can do. But I think the question is still very interesting.

LikeLike

The connection goes much further back. In the Bible and the Talmud, and presumably for early Christianity, intercourse was considered grounds for betrothal — thus, according to the law codes a virgin was an available woman because of her inexperience, and any other woman was either potentially taken or a prostitute.

LikeLike

“Virgo” (virgin) comes from the same root as “virga” (twig or shoot, or rod) but already in classical Latin they are very different words; when medieval writers make the connection, it’s largely accidental that they have hit on a somewhat accurate etymology, since most of their etymologies are pretty fanciful. Unrelated to “vir”.

The Latin term originally meant a woman who had never had sex, but could also be used for a young unmarried woman because they were supposed to be the same thing. (The English “maiden” worked the same way.) In that sense the sexual and the life-stage meanings “collided,” as you put it, in pre-Christian Rome–I would say “smushed” rather than “collided,” because rather than a moment of impact, there were centuries of fuzziness.

It is true that the unmarried state and lack of sexual activity were once (supposed to be) synonymous, but the French word “célibataire” for “bachelor” is not the proof, rather the fact that “celibate” has come in English to mean “sexually inactive” that is the proof. “Celibatus” in Latin means unmarried, and “celibate” meant the same thing in English until pretty recently (from the point of view of a medievalist anyway)–the 20th century so far as I can tell. The original OED does not give “sexually inactive” as a possible meaning, only “unmarried,” and alt When the Church today requires clerical celibacy, that means it requires priests not to marry. It also requires clerical chastity, but that is a separate thing. Priests who engage in sexual relations are not technically violating celibacy. However, in all the languages that use the term, “celibate” came to carry overtones of sexual abstinence because that was (theoretically) the appropriate behavior for the unmarried, and in English now “celibate” is commonly used for “sexually inactive.”

New Kid is 100% right on the difference between ideal and reality. What she is remembering is not just anecdotal, it comes from systematic quantitative study of marriage and baptismal records from the 16th century by folks in the Cambridge Group. That’s within 9 months from the church marriage, though, and people may have considered themselves informally married before that.

I don’t know of the term “virgin” being applied to men in pre-Christian Rome (Notorious PhD may know more than I on this point) but Christians in the Middle Ages did apply it to men, although it was much less important than for women. On male virginity I can recommend a good article: John Arnold, ‘The Labour of Continence: Masculinity and Virginity in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries’, in A. Bernau, R. Evans and S. Salih, eds, Medieval Virginities (University of Wales Press, 2003), pp. 102-18.

Sorry to go on for so long.

LikeLike

Slightly off topic, but ‘kanya’ in Sanskrit/most Indian languages means ‘virgin’ and is often explained away as ‘unmarried’. Interestingly, ‘kanya’ also means a girl who’s not reached menarche.

Probably because back when girls and boys were ‘promised’ to each other by their families at birth/soon after, their marriages were conducted before they turned 12, but the bride never went to her husband’s house until she started her periods, which is when she moved in with his family. (I’m guessing that was to prevent kids from serious making out until their bodies were ready).

LikeLike

Not much to add, Historiann. Previous commentators seem to have done the etymological homework for me; Hildegard von Bingen may (or may not) have had the etymological link between the “greening power” of the blooming branch (expressed in the verb “vireo”) and its etymological cousin, “virgo” in mind, when discussing “viriditas.” My Latin dictionary (which I wouldn’t necessarily trust) defines “virgo” as “(The blooming one: hence)…A maid, maiden, virgin.” Very sweet, as an etymology, actually, though perhaps not without its own ideological components.

“Virgin” comes into English, naturally enough, after the Norman Conquest, replacing the native word “maegden” and related forms, direct ancestor of ModE “maiden” of course. The ultimate English etymon appears to be “maegth” (apologies for not even attempting the Old English characters), which Clark Hall and Merrit identify as a “poetic” word (and hence, presumably archaic in both form and meaning, having largely dropped out of daily language). The poetic sense of “maegth” ranges across “maiden, virgin, girl, woman, wife” (CH and M cite a Gothic cognate, “magaths”; Old Saxon “magath” is glossed in The Heliand as “Jungfrau, Weib”). So in English/Germanic history, at least, the sense of the word seems to have undergone semantic narrowing, focussing in on youth and (eventually) what we call virginity. In Germanic languages, the etymologically related words have less to do with “greening power,” I might point out than to kinship structures, which may suggest that “wife” was the most archaic sense of “maegth”? But I’m not a real historical linguist.

LikeLike

A slight digression, but if I’m remembering correctly, the state of virginity was integral to notions of piety in late anitquity that carried over into the middle ages. Although they still denigrated the body, early theologians elevated women who were “intact” slighty above their non-virgin counterparts. This discourse concerns primarly nuns, but I believe that not ever having had sex was much more essential to cloistered women than to cloistered men. I want to say there is discussion of this in McClaughin, but I’m reaching back to grad school days, here, and it’s been a while!

LikeLike

Wow–thanks, everyone, for your informed responses (and corrections.) If it’s OK with all of you, I think I’ll go with the more “modern” (relatively speaking) definition of virgin as a never-married or not-yet-married woman when dealing with the Kindergartener.

It’s disappointing to learn how longstanding and deep is Western Christendom’s obsession with the concept of sexual “purity.” I’m not surprised, I suppose–I was just hoping for a little different trajectory, a moment of early medieval ambiguity…

LikeLike

Re: the explanation for the kindergartener, I’ll say this: my mom explained the virgin thing pretty concretely to me when I was around the same age. Basically, she tacked it on to the info she’d already given me about where babies come from, and she explained that the thing that made the birth of the baby Jesus a miracle and that made Mary miraculous was that Mary got pregnant with Jesus without there being any daddy. (Now, in the 21st century and not in a working-class, totally heteronormative catholic setting, you’d probably need to say “no daddy and no doctor to make her pregnant” or something like that.) So she surely didn’t go into the broader meaning of “virgin” as being about all sexual activity, but it was made very clear to me that Mary hadn’t done what it normally takes to get pregnant, however vaguely I understood it. I do have to say, though, I’m glad she gave me that much explanation, because I think it would have been weird to me if she’d said the thing that made Mary amazing was that she got pregnant with a baby without being married. Even in 1980 or so I knew people who had babies without being married, or who got married because they “had to” (ahem, my parents).

LikeLike

Sorry to come so late to this. I’m not nearly so learned as your other commenters, but I have a vague memory (sorry, I’m not at home right now, so I don’t have the references) that sources like Bachofen suggest that “virgin” means complete in herself. . . so it wasn’t lack of sex, but ability to be without a man. That’s in mythology, not Roman/Christian tradition, of course. But I’ve always liked it.

Then there is the silly scene at the end of Elizabeth I (the movie) where she re-virgins herself. By the mythic definition, this was never necessary.

LikeLike

I got so caught up in the scholarly part that I forgot the question was about what to tell a kindergartener . . .

I think the kid might find it confusing to be told a virgin is a woman who isn’t married, because the Virgin Mary *was* married. (And I won’t digress into medieval theology and canon law on that question–but consummation was not required for a valid marriage.) I wouldn’t say “she had a baby without a daddy or a doctor,” either, because those aren’t the only options. In my experience kids who are taught the ‘facts of life’ tend to focus on the sperm and the egg rather than how the sperm gets there, so if s/he knows the basics you could say that Mary had a baby without a sperm.

But if you want to explain to the child what it means in this context, without going into the biology of it, you could just say it means she was a woman chosen specially by God.

LikeLike

That’s an odd before meal prayer. The one I was taught is as follows:

Bless us O Lord,

And these thy gifts

Which we are about to receive

From thy bounty,

Through Christ Our Lord,

Amen.

It’s sufficiently standard that every Catholic I know knows it as “the Grace before meals” and it goes in the prayer book as “Grace Before Meals”. I never encountered the St. Michael Prayer as a Grace before and I’m cradle Catholic.

LikeLike

Kit–I think it was this child’s innovation, not something that ze was taught at school to do before meals.

And, Ruth–I think I’ll stay away from the particulars, and go with the vague theological explanation you suggest!

LikeLike

By chance, I recently read a review of a book on the history of virginity at Feminist Review. The book is called “Virgin: The Untouched History”, by Hanne Blank. Here’s the link to the review:

http://feministreview.blogspot.com/2008/05/virgin-untouched-history.html

As a young Catholic child used to reciting the “Hail Mary”, I recall asking my mother “what’s a womb and why is there fruit in it and why is Jesus a fruit?”

I can’t remember her answer. My recollection is that it was simply clear that it was not a question I ought to have asked. (circa late 1950s)

LikeLike

Hail Ruth, Tom, Servetus, and Squadromatico – great job on words!

LikeLike

hysperia, thanks for that link and the tip. I’ll have to check that one out.

“The fruit of thy womb” actually wasn’t a problem for us, since it’s just a metaphor for an actual biological process. That was easy–it’s the meaning of “virgin” that more difficult, in light of my modern problems with the concept as well as the multiple possible meanings detailed here.

LikeLike

In “A History of Celibacy” Elizabeth Abbott makes the case that in Roman times, well before Christianity was established, it was already believed that after menarche women were constitutionally incapable of overcoming their desire for children (women, of course, would *never* be interested in plain old sex.) On the other hand virginity was already highly esteemed so marriages tended to be arranged for daughters *very* early. That might account for Latin-derived associations of never had sex, unmarried, and young women. Side B of that in the face of such amoral desire for children virtue and chastity was supposed to fall to men. (Abbott says after marriage fidelity in women was still esteemed but abstinence for women wasn’t a priority.)

She also says that pagan Romans particularly marveled that Christian women could “mortify their flesh” by remaining virgins into adulthood, and that that became a big selling point for the power of piety. Her chapters on monastic early-Christian “desert fathers” recounts the sometimes extraordinary lengths pious men would go to to try and expunge sexual yearning.

For the record, in “Puritan Conscience and Modern Sexuality” Edmund Leites says it wasn’t till the Puritans that primary responsibility for chastity and moral virtue was offloaded on to women. Leites hints the shift was engineered so Puritan men could shirk sexual responsibility. (It was only a *shift* in blame since since of course women were already blamed for their alleged uncontrollable amorality in pursuit of pregnancy.) But I digress.

Anyway for a kindergartner it might be slightly more accurate, and maybe developmentally appropriate, to define a virgin as someone who hasn’t yet tried to be a mother or father.

LikeLike

It was possible to canonically regain ones virginity through a long enough period of chastity. There is an unintentionally amusing piece of praise poetry about an early medieval Irish bishop which praises him both for his virginity and his many fine children. . .

LikeLike

I feel that the “virgin mary” being described as never having sex… Only makes the whole Jesus story lose integrity. I mean… Who really ever believed that VIRGIN B. S. part of it anyways? I know I don’t and won’t believe it. Although to use virginThat statement makes the entire story more amazing and BELIEVABLE.

LikeLike

I meant to say too use virgin as unmarried…. Makes it more believable.

LikeLike